BirdTrack migration blog (20–26 October)

The last of the summer migrants have yet to depart, but their numbers are diminishing by the week as they move south. Swallows and House Martins are still being recorded, but it won’t be long before most have flown from our shores (although in 2022, up to 12 Swallows were recorded through the winter months in southerly regions of the UK).

Much to the delight of birders on the east coast, a spell of stronger easterly winds during the middle of the past week saw a variety of passage seabirds reported: Leach’s Petrels, Sabine’s Gulls, Sooty Shearwaters, Little Gulls and several skua species were seen from a number of watchpoints.

Winter migrants have started arriving in large numbers, escaping the colder temperatures further north and east. As with summer migrants arriving in the spring, certain species typically arrive earlier than others.

Teal and Wigeon numbers began to increase in September and earlier in October, and in recent weeks they have been joined by Pink-footed Geese from Iceland and eastern Greenland, Light-bellied Brent Geese from the Canadian Arctic, Greenland and Svalbard, and Dark-bellied Brent Geese from Siberia.

Tufted Duck numbers have been increasing as resident birds (those that spend all year in the UK) are joined by those from breeding grounds as far away as Iceland and arctic Russia. These flocks are always worth checking as they may contain other diving duck species such as Scaup, Goldeneye, or even Ring-necked Duck from North and Central America. Over a dozen of these rare but regular vagrants have been spotted in both Britain and Ireland in recent weeks, with some ‘regulars’ returning to their preferred wintering grounds which they visit every year.

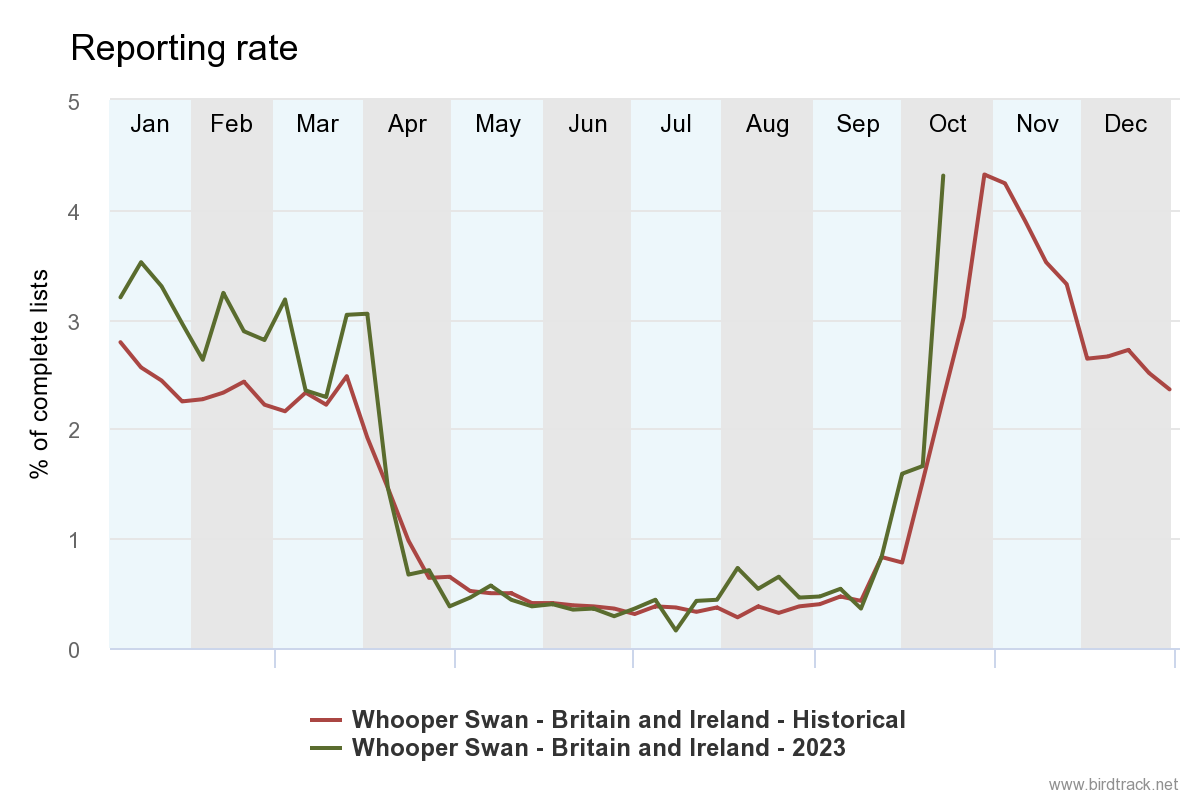

Reports of Whooper Swans have been greater than expected for this time of year. Birds may have taken advantage of the southerly tailwinds in the last week; these are favourable for this species’ migration, during which birds fly virtually non-stop from their Icelandic breeding grounds to Britain and Ireland. The tailwind greatly reduces the energy required to make this journey.

The Whooper Swan arrives roughly a month before its smaller ‘wild swan’ cousin, the Bewick’s Swan, which breeds further east in arctic Russia.

Redwings arrived in huge numbers earlier this month, with sightings of over 30,000 individuals in a single day at some migration hot spots on the east coast. More recently, the first pulse of Fieldfares also began to arrive; this species tends to arrive three to four weeks after the main arrival of Redwings. The Fieldfares’ chacking “blackjack” call could be heard as small groups arrived off the North Sea, having made the crossing from Fennoscandia.

Although Mistle Thrush might not spring to mind as a migratory species, breeding populations across much of north-eastern Europe also desert these freezing regions in winter and head south and west to warmer climes. Birds from these populations arrive in the UK during September and October in small groups of up to 10 birds, unlike the vast flocks of Redwing and Fieldfare that reach our shores.

Identifying winter thrushes: Redwing and Fieldfare

Redwing and Fieldfare may look similar at first glance, but with practice, it’s easy to tell them apart by appearance and by call.

The calmer, brighter days over the last week also resulted in widespread reports of Siskin, Chaffinch, redpolls (both Lesser and Common), and Goldfinches heading south in mixed flocks, some of which contained the occasional Hawfinch and Brambling.

For many, a flush of Waxwing sightings was enough to raise the question of whether we are in for a ‘Waxwing winter’ – a term used by birdwatchers to describe a year in which a particularly large arrival or ‘irruption’ of Waxwings reaches our shores. This magnificent punk rocker of the bird world is a firm favourite amongst birdwatchers, not only because of its beautiful plumage but also because it has a habit of turning up in residential areas where the relatively confiding birds feast on the berries of ornamental trees and shrubs.

Waxwings – the magnificent punk rockers of the bird world – are a firm favourite amongst birdwatchers, with beautiful plumage and a confiding habit.

The majority of recent sightings have come from Shetland, Orkney, the Outer Hebrides and mainland northern Scotland, but a few birds have made it as far west as Galway and as far south as North Norfolk. While reports aren’t above the historical average, it is encouraging to see birds arriving this early in the autumn.

A similar pattern occurred during the last big ‘irruption year’ in 2012; let us hope more arrive in the coming weeks. You can watch the live reports of Waxwing movements on EuroBirdPortal, and compare them to previous years. The movements of Waxwing in 2012 are particularly impressive.

October has always had the reputation of producing its fair share of rare and mega-rare species, and so far, the month has not disappointed. A Short-toed Treecreeper, a Continental relative of our more familiar Treecreeper, was seen in Kent, and an Upland Sandpiper made it all the way across the Atlantic to pitch in County Cork.

The second American Yellow Warbler of the year for Shetland graced gardens around Hoswick, while a Black-and-white Warbler entertained slightly smaller but no less appreciative crowds in Galway. This is the second record this year for Ireland, and incredibly, up to eight have been seen this autumn in Britain and Ireland. This makes 2023 the single best year for this species; the previous highest annual total was of four birds, in 1996.

Looking ahead

Easterly winds look set to extend into the weekend as a band of low-pressure moves across the southern half of the country towards the North Sea. Heavy showers and strong winds could ground migrant birds arriving from Fennoscandia along our eastern coasts as birds seek out cover from the weather. Seawatching on the North Sea should be productive if you can find some shelter from the weather; Pomarine Skua, Leach’s Petrel, Grey Phalarope, Sooty Shearwater, and Sabine’s Gull are all worth looking out for.

As the low pressure pulls away on Sunday, finer weather should follow. This will be a good time to check bushes for any passerine migrants that may have made landfall during the storm conditions.

Goldcrests, although small, are surprisingly tough: despite weighing only around 5 grams – the same as a 20 pence coin – thousands of these feisty birds migrate from Fennoscandia across the North Sea and to the UK each autumn. It was once believed that these birds hitched a ride on the back of migrating Woodcock, which made the same journey at a similar time of year. Any areas of scrub or woodland will be worth checking from Sunday; listen out for the calls of foraging tit flocks, which Goldcrests will often join.

These tit flocks are also worth checking for other ‘autumn sprites’: Firecrest and Yellow-browed Warbler may well be mixed in too, and you could even score something rarer like a Pallas’s Warbler. You can brush up on your ID skills in preparation for the commoner species with our Goldcrest and Firecrest Bird ID Video.

The number of Brambling migrating to the UK each year can vary, but generally, next week is considered the start of their main arrival period. The conditions over the early part of the weekend could see good numbers of these lovely birds. Listen out for their buzzing “tswairk” call, and keep an eye out for their white rump when they are in flight – both these features will help you distinguish them from the Chaffinches that will also be arriving.

So far this autumn, good numbers of Stonechats have been reported. These birds will be a mix of the hibernans race that breeds across Britain, Ireland and south-western Europe, and some rubicola race birds that breed in central and western Europe. These races can be difficult to tell apart during the autumn, but it is worth checking any Stonechat at this time of year to see if it is, in fact, a rarer relative: Siberian Stonechat and Amur Stonechat (formally known as Stejneger’s Stonechat) are both generally paler in colour than ‘our’ Stonechat and have a peachy wash to the rump.

Both Short-eared and Long-eared Owls arriving from the near-Continent can be seen during daylight hours in October, and are often seen flying out to sea, looking for a suitable place to make landfall. Corvids, especially Carrion Crows, Rooks and Jackdaws, frequently mob these owls, and busy groups of these birds can be a good way of locating an arriving owl.

As we move into next week, there will be a return to westerlies and rain as low-pressure systems arrive from the Atlantic. The heavy, more persistent bands of rain across much of Britain and Ireland will slow migration for a while, but it will still be worth looking out for migrants such as Golden Plover. Numbers will be building throughout October, and flocks can be found not only at coastal locations and estuaries but also on arable land, where they will often join Lapwing in large flocks. Their spangled winter plumage is duller than their striking summer finery: a mix of grey-brown feathering with only the wing, mantle, and tail feathers edged in golden yellow. This can make them difficult to spot in ploughed fields, and frequently, flocks are only noticed when they take flight to move from field to field. Again, these flocks are worth checking for rarer American and Pacific Golden Plovers; both these species are slightly smaller and longer-legged, and at this time of year, tend to be greyer in plumage with a more prominent stripe over the eye.

South-easterly winds look set to reach Shetland and Orkney at the start of the week, and this could be a recipe for a few exciting birds – maybe a Siberian Rubythroat, Siberian Blue Robin, or Rufous-tailed Robin will have a few people heading north.

By the middle of the week, low pressure will still be in charge of the weather, and at present, it looks like a spell of south and south-westerlies is forecast. If the winds stay light and the rain stays away, these will be good ‘visible migration’ conditions with finches being the main species group on the move. Siskin, redpolls (both Lesser and Common, although they are hard to separate when seen flying overhead), Chaffinch, and Goldfinch will make up the bulk of these birds, but look out for Brambling, Greenfinch, and, with luck, the occasional Hawfinch.

Possible rarities arriving on these winds include Pallid Swift, for which the majority of historical UK records are in late October and early November.

Send us your records with BirdTrack

Help us track the departures and arrivals of migrating birds by submitting your sightings to BirdTrack.

It's quick and easy, and signing up to BirdTrack also allows you to explore trends, reports and recent records in your area.

Find out more

Share this page