Sharing our gull tracking expertise in a study of Dublin’s ‘noisy neighbours’

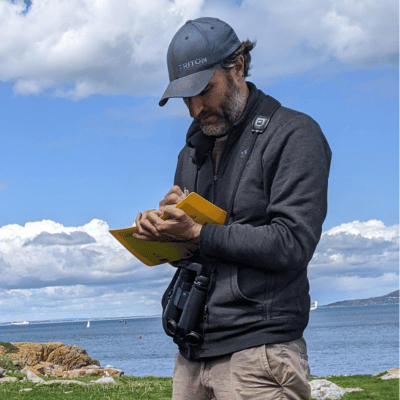

PhD student Jon Willans takes us through his fascination with gulls and his fieldwork, which was supported by our scientists.

“Why would you want to study seagulls?”

“Those birds are pests — they don’t even belong in cities.”

“They are so noisy!”

These are just some of the comments I have heard after people learn that I am a PhD student studying the movement ecology of urban gulls. It turns out that, apparently, not everyone likes gulls or finds them as interesting as I do.

Here in Dublin, like in many coastal cities around Ireland and the UK, there has been a noticeable increase in the number of nesting gulls over the past 30 years. Unfortunately for the gulls, they haven’t been universally welcomed with open arms.

Some human residents feel that the addition of gulls to urban areas should be looked at as a cause for concern and outrage, rather than celebrated as a boost to gull populations — despite drastic declines in gull numbers that have led to some species being listed as of significant conservation concern in Ireland. And human–gull conflict is a growing issue in some cities, where officials are increasingly being pressured into action to control bird numbers by means such as egg oiling, nest removal and even culling.

But, as urban-nesting gulls are a relatively new phenomenon, little is known about how these birds are using these urban environments. Do urban-nesting birds even use the sea? Do they leave the city at all? How does their movement differ from ‘natural’ coastal nesting gulls? Do these coastal-nesting birds generally use the marine habitat for foraging, or do they also spend large amounts of time in the city to find food? The answers to these questions are extremely important when it comes to making any decisions about gull population management.

Urban nesting gulls are a relatively new phenomenon, so little is known about how these birds are using their environment.

An introduction to our research

It was these questions which brought our team, consisting of researchers from University College Dublin (UCD), BirdWatch Ireland, the Irish Midlands Ringing Group and the British Trust for Ornithology, to Ireland at the end of May, to try and shed some light on the movement of locally breeding Herring Gulls.

Specifically, in this study, we wanted to investigate whether there is a difference in the movement ecology — how birds navigate through habitats, and where they go — between birds nesting in urban spaces and on islands around the coast. To determine this, we needed to find both an inland colony and a coastal colony of nesting gulls, and attach GPS units to individual birds. We could then analyse data from birds in the two colony locations to see if or how these birds differ in their use of Dublin’s urban landscape.

Tracking urban gulls ...

The first stop for the team was the UCD campus in south Dublin — our urban study site — where a small but increasing community of Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gulls can be found nesting on many of the rooftops around the university. While this type of environment is not traditionally associated with ideal habitat for nesting gulls, when you look closer you notice that the campus has everything that the gulls might require.

The tall buildings act as cliffs, where gulls can make their nests with an unobstructed view of their environment, safe from most predators. The many ponds and sports fields on and around the campus provide an ample amount of water and natural feeding opportunities.

A plentiful supply of food is also provided by the thousands of students and staff that make the daily trip onto the campus. On any given day, particularly when the sun is shining, hundreds of people can be found sitting outside eating. Gulls are often fed by these people, but they are also known to snatch food from unsuspecting diners when their hints for a snack are not being met accordingly. The gulls also feast on the mess that is left behind after people have moved on, which sometimes includes pulling rubbish from bins in search of a quick meal. Indeed, some may say this is an urban sanctuary for these birds.

The goal of our team was to catch some of the local birds and attach lightweight GPS units to them, which would give us some information about how these birds are using their environments.

The goal of our team was to catch some of the local birds and attach lightweight GPS units to them, which would give us some information about how these birds are using their urban environments. Over the next two days, working on four different rooftops and spending a considerable amount of time waiting for the unsuspecting birds to walk into the carefully placed, specialist traps, we managed to catch six breeding Herring Gulls.

Once we had taken the birds safely out of the traps, the team went into action. The birds were weighed, and we collected morphometric data like wing, bill and head length. Then we attached uniquely coded rings to their legs and fitted them with their solar-powered GPS units. These units gather and transmit data about the birds’ location and movement speed, which we can use to identify the birds’ behaviours — such as foraging, feeding or resting — as the birds navigate around the landscape.

With six tags deployed and each one actively collecting data, stage one of this mission was complete. We had tagged our urban birds.

... and coastal gulls

Stage two involved moving operations to Dalkey Island, some 10 km to the south-east of UCD as the gull flies.

Although the island is only separated from the mainland by approximately 350 m, after getting off the ferry it felt like stepping into another world. From the herd of Old Irish goats that stopped their grazing to observe us as we arrived on their island, to the sound of the breeding gulls and the buzzing Arctic Terns that nest there, it couldn't have been further removed from the university campus.

Dalkey Island is a more traditional place to find breeding gulls: a rocky coastal area with some scrubby turf and thrift, and plenty of nooks and ledges to make a scrape-like nest. The island has large nesting colonies of Herring, Great Black-backed and Lesser Black-backed Gulls, and when we visited, pairs were scattered all across the island’s east side. Segregated zones marked the presence of the different species: while the massive and intimidating Great Black-backs watched from up high on the grassy slopes, the Herring Gulls were lower down and mainly confined to the rocky areas near the shore and the Lesser Black-backs were scattered at the north end of the colony.

We set more traps and over the next two days, seven more Herring Gulls were caught and selected to collect data for us, fitted with GPS units and sent on their way. Now we had our coastal nesting birds as well. Job done! Well, almost ...

What will we learn about Dublin’s ‘noisy neighbours’?

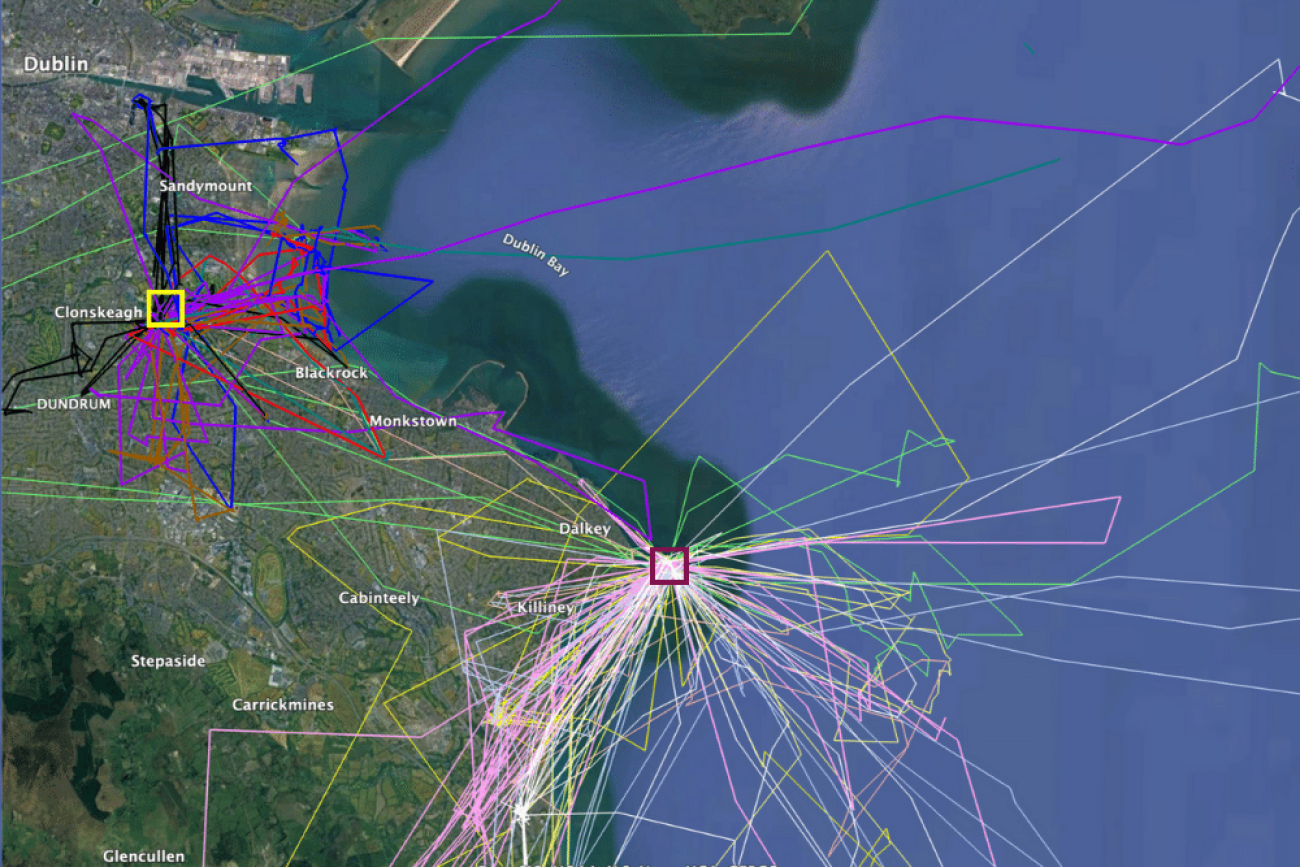

Early data returns from the GPS units show that there may well be differences in the way these groups of birds behave and use the urban landscape.

Over the next two years, all the GPS tags that the team has worked so hard, and suffered so many bitten fingers, to deploy will be transmitting data back to us and revealing just exactly how the gulls spend their time as they move around this country and perhaps even further afield.

The next step in the research involves analysing all this information. Early data returns from the GPS units show that there may well be differences in the way the urban- and coastal-nesting birds behave and use the urban landscape. As expected, both groups of birds spend a great deal of time inland, visiting the downtown core and the suburbs around the city. However, one initial difference appears to be the birds’ use of the sea: coastal nesting birds make frequent feeding trips out to sea, while the urban nesting birds seldom use this resource and appear to be full-time city dwellers.

Is the sea in ‘seagull’ even applicable to all of these birds? As the data they have unknowingly collected are analysed, all will be revealed — and I for one cannot wait.

The tags deployed over this week of fieldwork will continue to record the movements of these gulls until the specially-designed harnesses break apart and relieve the birds of their GPS units.

What secrets will these data reveal? Is the sea in ‘seagull’ even applicable to all of these birds? These secrets will remain with our gulls for the meantime, but soon, as these birds move around on their daily adventures and the data they have unknowingly collected are analysed, all will be revealed — and I for one cannot wait.

Help us monitor gulls this winter

If you are confident identifying the six main species of gull found in the UK in winter — Herring, Lesser Black-backed, Great Black-backed, Black-headed, Common and Mediterranean — you could join our Winter Gull Survey.

Volunteers will only need to make a small number of visits to gull roosts between 2023 and 2025, but their contributions will help us fill in vital gaps in our understanding of these Amber- and Red-listed species.

How to take part in WinGS

Share this page