What have the Cuckoos taught us?

Relates to projects

Related Publications

The only information we had was from an old ringing recovery: a Cuckoo, ringed as a chick in a Pied Wagtail nest in Berkshire in the summer of 1929, was taken for the pot in Cameroon on January 30, 1930. There are two things to note about this:

Firstly, the person that took this Cuckoo had the presence of mind to return the ring to the BTO – if they hadn’t, we wouldn’t have had this piece in the Cuckoo jigsaw.

Secondly, it was taken in mid-winter. So, might Cameroon be the wintering area for our Cuckoos? It was unsafe to assume so, based on only one record, but there was a very good chance that it might be the case.

The birth of the Cuckoo Tracking Project

Fast forward to 2011 – our Cuckoos are in trouble, the UK breeding population down by over half during the last 25 years. We know a great deal about our Cuckoos whilst they are here in the UK, and the hosts that they use, mainly Reed Warbler, Meadow Pipit, Wren, Dunnock and Pied Wagtail. All of these species are doing much better than our Cuckoos, so there should be plenty of hosts to go around.

What we needed to know with more precision is where the Cuckoos spent the winter months, the routes they took to get there, and where they stopped to rest and refuel for their onward migration.

Senior BTO Research Ecologist Dr Chris Hewson was at this time aware of new lightweight satellite tags that could, with the right licensing permissions, be fitted to a Cuckoo.

These tiny transmitters – known officially as Platform Transmitting Terminals or PTT tags – alternate between 10 hours of activity, in which their location can be detected by satellites, and around 48 hours of ‘powering down’, when a small solar panel recharges the tag’s lightweight battery.

After a successful proposal, which obtained the necessary permissions, Dr Hewson set about raising funds for the tags; these cost around £3,000 each. Thanks to support from the BBC, it was possible to fund the BTO Cuckoo project for its first year.

The project fledges …

Five tags were purchased and fitted to the first five Cuckoos of the project: Chris, Kasper, Martin, Clement and Lyster, all caught and ringed in East Anglia. The satellite data from the tags were available immediately, allowing Chris and others at BTO to follow the Cuckoos’ every move.

BTO launched the project to the public, asking them to sponsor their favourite bird. Thanks to the response, which was immediate and much greater than anticipated, the project was secured financially and our attention turned in full to the Cuckoos.

… and spreads its wings

BTO followed all five Cuckoos as they moved around their breeding areas, and then came the first big surprise – by the first week of June, the birds were beginning to leave the UK.

This was much earlier than expected; the average arrival date for the Cuckoo in the UK is April 19th, which meant that some of these birds had only been in the country for around six weeks before heading off!

Before the project started, we had a few ringing recoveries from northern Italy, which suggested this area was a stopover site for migrating Cuckoos, and, as expected, three of the birds took a route via this region.

However, two of the birds took a western route via Spain. This was brand new to science, a new discovery – there has never been a British-ringed Cuckoo recovered in the Iberian Peninsula.

On leaving the Po Basin, the birds in Italy undertook long flights across the Sahara, stopping near the southern shores of Lake Chad before heading further south into the Congo Basin and the Congo Rainforest.

Chris had predicted this, but for the first time, he could now confirm where some British Cuckoos spent the winter, and how they get there. But what of the other two birds?

Having rested and refuelled in southern Spain, they too headed south across the Sahara to Côte d’Ivoire and the tropical rainforest belt. The habitat here is very similar to that in the Congo Rainforest, where the three birds that took the Italian route were wintering, but the birds that took the Spanish route didn’t stop.

Instead, they flew east, crossing West Africa to join the birds already in the Congo Basin. Despite arriving in the same wintering grounds, their journey was 1,500 km longer than the birds that had refuelled in Italy. We have since tagged nearly 100 Cuckoos and all of them have wintered in and around this area.

Watching the return

So, we had an answer – British Cuckoos were spending the winter, or at least part of it, in the Congo rainforest. But what about the return journey? Might they just simply head north from the Congo Basin and cross the desert via Chad and Libya? We really didn’t know.

What they actually did was head northwest around mid-January, passing through Gabon, Cameroon and Nigeria. Remember that ringing recovery from the end of January in Cameroon?

It is highly likely that this bird was on migration through the country when it was caught, not spending the winter there. The birds then moved west towards Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, all five of them, where they stopped to rest and refuel for the northward desert crossing.

All our tagged Cuckoos, irrespective of the route they took on their southward migration, travelled back to the UK via West Africa – another new discovery. From West Africa, they head north across the desert, covering the 2,000 miles in a single, non-stop flight which brings them to the Iberian Peninsula, and, after a brief pause to refuel, back to the UK.

The tagged Cuckoos’ legacy: data, data, data

There are numerous hazards during such a long journey. On their round trip of around 10,000 miles, Cuckoos face drought and high winds, hail, sand and thunderstorms, and lengthy sea crossings.

One of our Cuckoos returned to the North York Moors to find them covered in snow – not ideal conditions for a bird that spends most of its time in the tropics! Unfortunately, it succumbed, but this is important information – not only do we want to know what these birds are doing, but we also want to know where they perish and, if possible, why. This information will help uncover the driving forces behind the Cuckoo’s decline in the UK.

Since we followed the first five Cuckoos to the Congo and back, we have watched almost a hundred birds make their twice-yearly journeys to their wintering grounds. We’ve tagged birds in locations across the UK, from Thetford Forest in Norfolk to the Kinloch Hills on the Isle of Skye.

We’ve learnt that Cuckoos can cross 1,000 miles of ocean without stopping, and can make a U-turn during their annual migrations if conditions for refuelling 100 miles previously were more favourable. And we’ve also learnt that the migration route the birds take is strongly correlated with their survival.

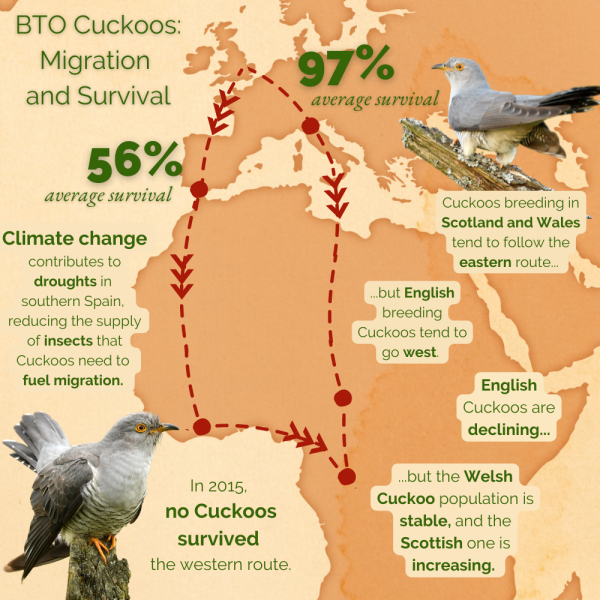

In some years, tagged Cuckoos taking the Italian route to their wintering grounds showed a 97% survival rate, compared to only 56% via the Spanish route. This difference in survival was cemented before the birds left Europe, suggesting that the Cuckoos storing up fat in the western part of the Mediterranean to fuel their migratory flight onward might be finding this harder to do than those in the east.

This could be due to climate change, which is contributing to summer droughts in Spain and the consequent reduction in numbers of the high-energy invertebrates which the Cuckoos feed on. In 2015, none of the Cuckoos passing through Spain survived.

Additionally, analysis has also shown that the proportion of birds using the less successful route via Spain correlates strongly with the pattern of local population decline within different parts of the UK.

Cuckoos following the western route on their autumn migration tend to breed in England, where Cuckoo declines are especially severe, whereas birds following the eastern route tend to breed in Scotland and Wales, where Cuckoos are increasing and stable respectively.

While most birds follow the same routes year after year, PJ became the first tagged Cuckoo to use both the eastern and western route, as well as a new route in between, even stopping in both Spain and Italy in one journey south. This flexibility could be key to his long life, helping him avoid the worst conditions and stop off at the best feeding grounds.

Questions, questions, questions

The timing of migration can be governed by different mechanisms, divided broadly into ‘endogenous control’ (internal cues, such as those genetically programmed into species) and ‘exogenous control’ (external cues, such as day length or rainfall).

Species which are very consistent in the timing of their migration are usually more dependent on endogenous cues, which do not change from year to year. However, the tagged Cuckoos show a fair level of variation in their departure from Africa, suggesting they are responding to an environmental cue which is not consistent between years.

Chris is currently investigating how the Cuckoos interact with the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ); this is the area where the southeast and northwest trade winds converge, visible in the form of a band of clouds and thunderstorms encircling the Earth near the Equator.

The ITCZ brings important rains to West Africa in early March, and causes a spike in vital invertebrate food sources for the Cuckoos. Using data from satellite-tagged Cuckoos, we will be able to discover whether the timing of this rainfall affects when the Cuckoos begin their northward migration.

Why is this important? The timing of the Cuckoos’ journey may affect the availability of food later on in their journey, as well as how likely the birds are to encounter hazards like storms or drought. This in turn will affect their survival.

Chris is preparing several scientific papers which describe his research, including updated information on the drivers of Cuckoo declines.

In the meantime, you can follow our Cuckoos at www.bto.org/cuckoos and watch as the latest cohort makes its way south, building on a legacy of almost a hundred birds before them.

Class of 2023

Follow this year's cohort on their migration to the Congo Basin and back.

Share this page