Songbird migration across the Sahara

Mark Wilson, BTO Research Ecologist, reflects on his work tagging songbirds to collect data about their migration routes over the Sahara.

Mark is responsible for developing and leading research, and contributes to the scientific strategy of BTO Scotland. He manages a small and brilliant team of three research and fieldwork staff, and is involved in several BTO projects and external collaborations carrying out research and monitoring work on a wide range of topics including upland and woodland ecology, breeding waders, raptors and acoustic monitoring.

Relates to projects

I slowly open my hands. The male Tree Pipit I am holding crouches for a moment, before giving a little shake and leaping from my cupped palm, zipping down the wooded slope and landing in a tall birch about 10 m away. He checks out the new colour rings on his leg, which allow him to be identified without being recaptured. A few minutes later, as I am putting away my equipment, I hear him burst briefly into song before he disappears into the trees.

This Tree Pipit is one of dozens of birds that BTO colleagues and I have been fitting with miniaturised geolocator ‘backpacks’. From the information collected by these clever little tags, it’s possible to work out where the birds wearing them have gone.

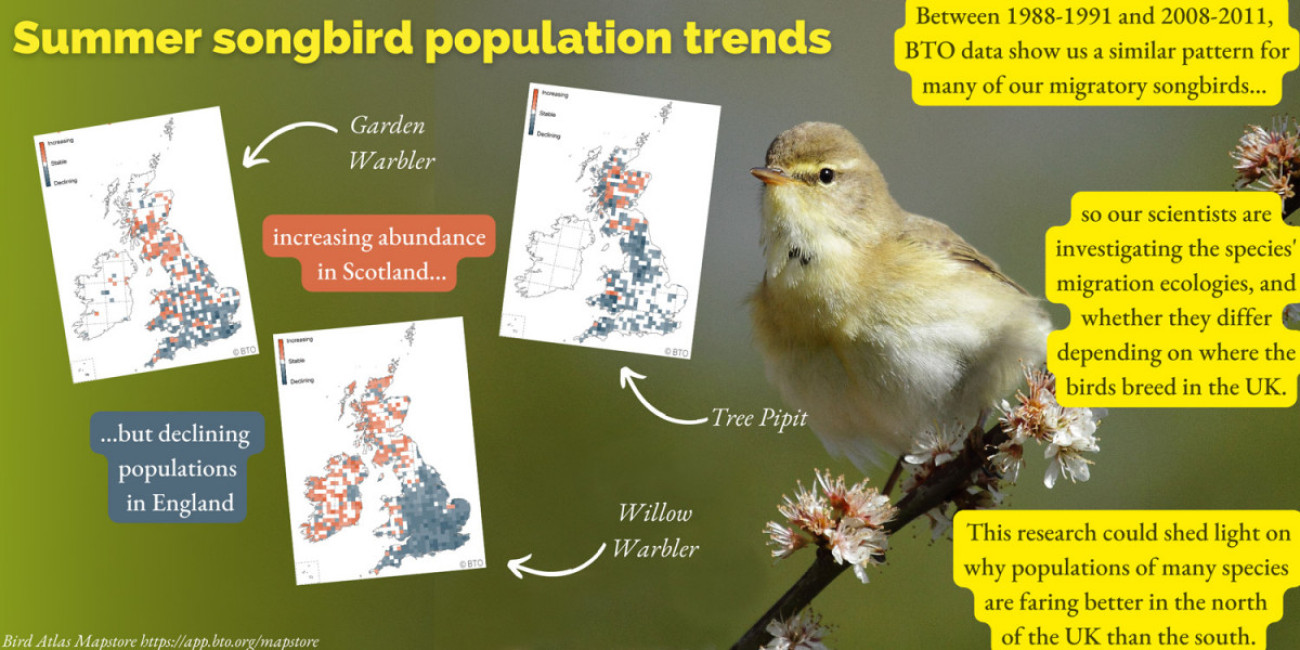

As well as Tree Pipits, we are fitting tags to five other migratory species which breed in the UK but spend their winters in sub-Saharan Africa: Garden, Wood and Willow Warblers, Whinchats and Spotted Flycatchers. Of these, Wood Warblers and Whinchats are declining across the whole of their British ranges, while the rest are all declining in the south of Britain, but faring better in the north.

Our project has tagged birds of all six species, first in central and southern England, and now where I am based, in the hills, woods and gardens of central Scotland. We hope the results will reveal whether the migration ecologies of these birds could be contributing to recent declines, and maybe help us to understand the differing fortunes of northern and southern populations.

The sound of summer

Listen to the recordings we use in the field.

Tree Pipit

Willow Warbler

Wood Warbler

Whinchat

Garden Warbler

Before a bird can be tagged, it must be caught. Once a mist net is up, we will put a portable audio speaker below it and play the songs and calls of one or more of the species we are trying to catch. By doing this, we simulate a territorial incursion by a rival male. The idea is that the resident male will fly over to the recording to check it out and be caught in the mist-net. When trying to catch Wood Warblers, the recording has sometimes been playing for less than a minute before the target bird is in the net!

Of course, it’s not always that straightforward. We are all familiar with differences between species in how they look, what they sound like, and where they live. But birds also differ from each other in their personalities.

Willow and Wood Warblers typically respond strongly and rapidly to playback, but Tree Pipits and Whinchats often display more caution. Our colleague John, who has worked on Whinchats for many years, estimates that it normally takes about 25 minutes to catch a Whinchat using a sound recording to lure it into a net. Oddly, Whinchats can show every sign of knowing a net is there, looking at it, flying around it, even perching on it – before eventually flying into it!

In comparison to the other species, Garden Warblers can be very difficult to catch, displaying even greater caution than Whinchats. A typical Garden Warbler may respond to playback not by charging in to check out who the intruder is, but by flying a short distance away and singing back to the tape from cover.

The trickiest of these species to catch in mist-nets, though, is the Spotted Flycatcher, due to their acute eyesight and phenomenal aerial agility. Most Spotted Flycatchers respond even less strongly to playback of their ‘song’ (a high-pitched, two-toned squeak that, at least to the human ear, sounds rather understated) than Garden Warblers do. To catch these birds, we rely on their well-known habit of repeatedly returning to favourite perches after flying off to catch insects. Accordingly, we catch Spotted Flycatchers using special ‘perch traps’, placed in what we judge to be tempting places for them to perch.

There can be almost as much variation in personality within a species as there is between species. Some Wood Warblers keep their distance from the simulated breach of their territories, staying high in the canopy, or respond to audio playback by flying away from it! Timing makes a difference, too. Most males are easier to catch early in the season, when they are defending newly established territories, striving to outdo their neighbours’ efforts to attract a female or even, once they have paired, jealously guarding fertile mates against the chance that an intruding male might convince her to be unfaithful. Later in the season, when their mates are incubating eggs, or when eggs have hatched and there are chicks to feed, many males seem (understandably) much less bothered at the prospect of a male, presumably late arriving and unpaired, belatedly trying to persuade their female into a liaison.

Once we’ve caught a bird that we are going to deploy a tag on, it’s all systems go! Keeping the time taken to ring, measure and tag the bird to a minimum reduces the amount of stress it experiences. As well as fitting a standard metal ring with a unique identification code on one leg (just as we would with any bird we ring), we also fit a unique combination of coloured plastic rings allowing individuals to be recognised in the field. We measure the weight of each bird, and the length of its wings and tarsi (the ‘leg’). Tagged birds are then fitted with a geolocator’ backpack’, attached via a pre-sized leg loop harness. We select which tag to deploy based on the size of the bird, checking that the fit is good before the bird is released. We monitor the birds closely throughout, only fitting tags when their stress levels remain relatively low. A portion of birds, referred to as ‘controls’, are left untagged. We fit colour rings to these control birds so we can compare the return rates of our tagged birds with those of untagged (but individually recognisable) birds.

Releasing a Whinchat Glen Finglas, the Trossachs

Many large remote-tracking devices transmit the data they collect remotely to researchers, without the tagged birds ever being seen again. However, smaller geolocator tags store all the information they collect ‘on board’. This means that in order to learn where tagged birds have gone, they must be recaptured on their return to us, so we can retrieve their backpacks. This year was the second year of this project in Scotland, and the first in which we have started to retrieve geolocators from tagged birds. Unfortunately, return rates seem to be lower than normal, and not many of last year’s tagged or control birds have been seen. The fact that the proportion of returned control birds is at least as low as that for tagged birds, as well as information from other sources such as BirdTrack, suggests that the low return rates aren’t being caused by the tags. Although this makes it harder to get many of the tags back, we do have some, and will keep trying to find and retrieve more. Every tag that we do retrieve can tell us lots about migration timings, routes and stops, as well as movements on the wintering grounds.

Without the generous help and support of all these volunteers, projects like this would be much harder.

This is a rewarding project to contribute to. Over the past two years, many people have generously contributed their skills, knowledge and, in the case of Spotted Flycatchers, gardens, in order to benefit this project. Going back to visit last year’s Spotted Flycatcher ‘hosts’, in whose gardens we caught birds, will be a particular pleasure this year. Without the generous help and support of all these volunteers, projects like this would be much harder.

All of these species are special, and it is a privilege to work with them...it’s great to know that this project could help us to understand migrant declines and, more importantly, work out what we can do about them.

An added bonus of spending long hours doing pretty much any kind of fieldwork is that days are inevitably enriched with generous helpings of ‘non-target’ wildlife. During our fieldwork we’ve stumbled across Roe Deer fawns hiding in bracken, inadvertently flushed Black Grouse off a road onto the roof of a nearby cottage, found unexpected nests of Wood Warblers, Willow Warblers, Whinchat, Grey Wagtails and Snipe, come across Canada Goose goslings bimbling through a woodland for their first swim, watched an Osprey being mobbed by irate Common Gulls and viewed a White-tailed Eagle sailing over the hills. It’s occasionally been a great engagement opportunity too, with lucky walkers being greeted by a bedraggled ornithologist doing an impromptu bird ringing demonstration. One couple on holiday in Scotland from Israel were especially thrilled to see a Whinchat be released back into the bracken, and probably left wondering what other mad things Scots get up to in the morning!

But for me, the best thing about this project is its main focus – the woodland migrants whose journeys we are hoping this work will help us to understand better. All of these species are special, and a privilege to work on. Not many people get to spend so much time around breeding Wood Warblers, Whinchats, Tree Pipits and Spotted Flycatchers; even fewer get the chance to see these beautiful birds in the hand. Garden Warblers may be more familiar to many British birders, but this is a species that was, until recently, uncommon in central Scotland. It is still patchily distributed here, and it’s a pleasure for me to spend more time with it. And although Willow Warblers are still among the commonest summer visitors to many parts of Scotland, they have declined alarmingly in most other parts of Britain. We can’t take their continued abundance here for granted. It’s great to know that this project could help us to understand migrant declines and, more importantly, work out what we can do about them.

Share this page