Arctic Skua migration: stories from the field

Helen and David Aiton take us through their fieldwork seasons for BTO’s Arctic Skua tracking project.

Where do Arctic Skuas go when they are not here?

For us, ‘here’ is Rousay, an island which lies off the West Mainland of Orkney. We have been measuring the breeding success of Arctic Skuas since 2014, and working with BTO to help track the adult birds’ migration since 2018.

We were drawn to these beautiful birds by their plaintive calls, their stunning range of plumages and – sadly – their rapid population decline. In 1991, there were 122 pairs in our study area along with thousands of Arctic Terns. Now, in 2023, there are only 17 Arctic Skua pairs and a mere handful of breeding Arctic Terns. This trend reflects that of the UK breeding population more broadly, which is restricted to north and west Scotland and has declined by 70% since 2000.

Our fieldwork site is a triangular area of coastal moorland approximately 2 km by 1.5 km and varies from 5–115 m above sea level. We also research Great Skuas in our study area – but that is a story for another time! The aim of our long-term study is to monitor how both skua species are faring in these turbulent times.

This year, 2023, was the 10th season of our Arctic Skua productivity study, which measures the breeding success of the colony. We collect information about the number of eggs, chicks and fledged young every breeding season. Over the past 10 years, our colony has fledged 96 juvenile birds.

Fieldwork on Rousay

Each year we visit the study area at least eight times, an effort of 16 days minimum. The island can be reached by a 30-minute ferry trip, crossing the beautiful Eynhallow Sound. Our fieldwork is made more comfortable in our old VW Campervan for overnight stays.

We locate nests at the start of each breeding season from vantage points at least 200 metres away: one person remains at the vantage point and directs the other using radios, to as many as five nests at a time. Arctic Skua nests are well hidden, so we have to use sightlines and surrounding vegetation to memorise their positions, so we can monitor them throughout the season.

Arctic Skua nests are well hidden, so we have to use sightlines and surrounding vegetation to memorise their positions.

We also use our two highly-trained German Shorthaired Pointers to increase the efficiency of finding chicks which have become more mobile and might have wandered away from the nest. It’s very important that we only undertake nest and chick finding in dry, warm weather to avoid the risk of causing any harm due to chilling.

The Arctic Skua tracking project

Liz Humphreys from BTO Scotland contacted us in 2018, having heard about our well-established study. BTO’s scientists were keen to use geolocators to track the adult Arctic Skuas, to find out where they spent their winters, and to learn more about their migration routes. This information would help inform conservation efforts to protect this species. The work on Rousay would build on the study of Fair Isle breeding Arctic Skuas, which BTO began in 2017, and offer a comparator site. Fair Isle is roughly 30 miles from Orkney.

BTO’s Senior Research Ecologist John Callandine joined us for a week on Rousay, arriving in late May 2018. Luckily for John, we had a week of hot, dry and still weather, almost unknown in Orkney – highly suitable conditions for checking nests and catching adult birds for tagging. He was delighted that we had already located the nesting birds.

Luckily, we had a week of hot, dry and still weather, almost unknown in Orkney – highly suitable conditions for checking nests and catching adult birds for tagging.

For the tagging project, we chose mostly well-established pairs of adult birds. Over the next few days, we watched the birds and waited for them to lay a full clutch of eggs. We then prepared the walk-in traps – safe structures for catching the adult birds – and left them for a couple of days near the nests, to habituate the birds to them.

Eventually, we placed the traps over the nests, to catch the adults as they walked onto the nest to incubate the eggs. To keep the eggs safe from predators while we tagged the adults, we removed them temporarily and replaced them with dummy eggs before putting the walk-in trap over the nest.

John had honed the techniques for catching birds on Fair Isle the year before, so we were a slick team! We caught 10 individual birds, two of which were a pair. As soon as the tagging was finished we replaced the real eggs. The whole process never took more than an hour.

John then left Rousay to go to Fair Isle to catch more birds, and we continued our study for the rest of the summer. It was reassuring that the birds with geolocators continued to behave normally, with most of them rearing chicks successfully that year.

Collecting the geolocator data

Using geolocators as a tool to understand migration routes does not provide instant gratification. To collect the data from the geolocators, they have to be retrieved from the birds, which meant we had to catch the tagged birds again to get any information at all! Innocent of the wiles and intelligence of Arctic Skuas we returned to Rousay in late spring 2019, keenly anticipating retrieving the geolocators and continuing our productivity study.

John joined us again in early June to begin the retrieval process and repeat the procedure using the walk-in traps. However, of the 10 birds we caught in 2018, only eight birds had returned, and one of the birds that did return tried to breed, but her nest failed before we had a chance to try to recapture her with the walk-in traps – down to seven birds.

Arctic Skuas share incubation duties, with both the male and the female sitting on eggs. Because individual Arctic Skuas can occur in one of two plumage types – birds are either ‘dark’ or ‘pale’ phase – we could tell the male and female apart if they had different phase plumage, what we called a ‘dark-pale phase pair combination’. But for a dark-dark phase pair combination, where only one of the pair was carrying a geolocator, we had to take extra care to ensure we were catching the right bird.

The first bird we tried to catch, a female pale-phase bird, walked straight into the walk-in trap and onto the dummy eggs – hurrah – Geolocator Number 1. After this, we thought – this was going to be easy! Alas not. That was the only geolocator retrieved during John’s visit, despite trying for the remaining six birds who all refused to go back into a walk-in trap.

Later in June, we tried mist-netting one pair that had a young chick. A mist net is a fine mesh held taut between two vertical poles, which we can use to safely catch birds by encouraging them to fly or walk into it (in this case, by placing a stuffed predator close by to the net in the hope that the adult birds would fly into the net while mobbing it) but the adults very cleverly called the chick away from the net instead. Sigh!

We were fortunate that one pair – which had had a single egg predated by a neighbouring Arctic Skua (quite common in the skua colonies) – re-laid, and had a young chick less than a week old in late July. With both adults close to their nest, we had the opportunity to try recatching them, and this time both threw themselves into the mist net at the same time! Geolocator Number 2 retrieved.

As in 2018, the colony went on to successfully fledge chicks, including that late chick.

A brief hiatus ...

Due to COVID-19 restrictions in 2020, we were not able to return to Rousay until early July, by which time the chicks were too old for us to try to catch the adults with a mist net. Again, though, it was a good year for the Arctic Skuas and they fledged at least 10 chicks.

... before fieldwork resumed

In 2021, three years after putting the geolocators on the birds, John joined us again in glorious weather in early June. There were still four birds with geolocators breeding in the colony. We successfully mist-netted a female using dummy eggs and a stuffed predator, which she duly mobbed and entered the mist net – Geolocator Number 3 retrieved.

John and David worked very hard to retrieve the remaining three geolocators, but the birds refused to engage with the walk-in traps or the mist nets. Later in June, we tried again with the dark-phase male mate of the first pale-phase bird we retrapped in 2019 – and success! – he eventually walked into the trap and settled on the dummy eggs – Geolocator Number 4. We hoped at the very least that the birds we recaught to retrieve the geolocators this year would give us two years’ worth of migration information.

Finally, after approximately 200 hours of effort, we had four geolocators retrieved, along with six geolocators from John’s work on Fair Isle. The BTO team could set about retrieving the data from the geolocators and plotting the migration routes of the 10 Arctic Skuas. It is no exaggeration that we were all thrilled to see the results.

Migration stories revealed

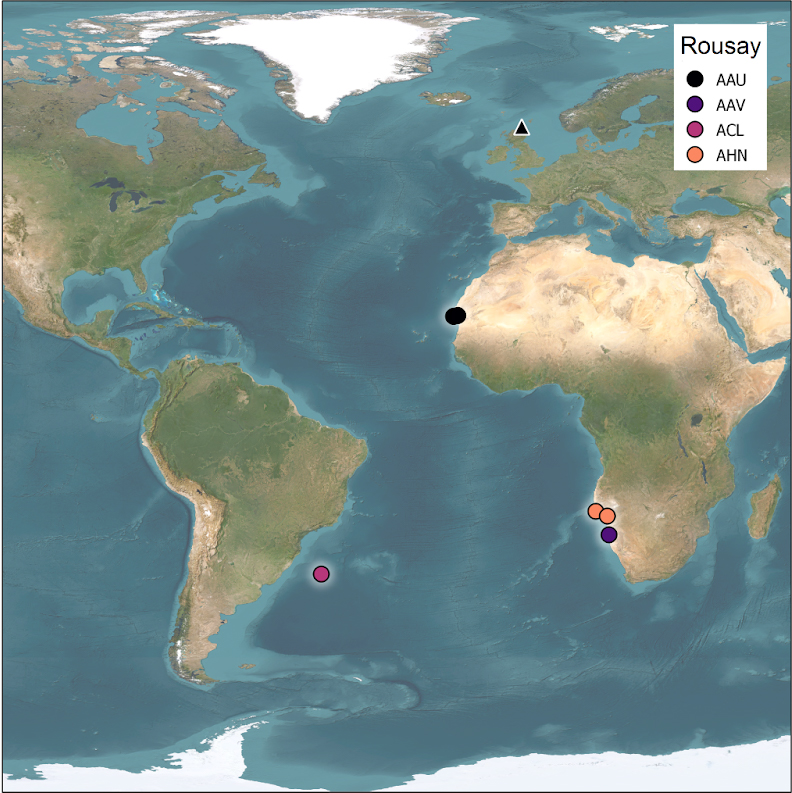

The data showed that all the Arctic Skuas travelled south via the North Sea and English Channel. Then down past France, Spain and Portugal to the coast of north-west Africa and on to their wintering grounds.

Individual Arctic Skuas wintered in different locations: off the coast of north-west Africa, the coast of south-west Africa or the east coast of South America. The accuracy of the data is roughly to the nearest 200 km so the birds are not actually on land, as can appear in the maps of the location points – they overwinter at sea. The birds that had data over two winters went back to the same area each year. Astonishingly, our pair of birds that both had geolocators went to different continents!

The work we did in Scotland will also be part of a multi-colony study of Arctic Skua wintering and migration movement involving colonies right across their north-east Atlantic breeding range – some of which was presented by BTO Senior Research Ecologist Nina O’Hanlon to the International Seabird Group Conference in Cork in September 2022 and has now been submitted for peer review. You can read more about the project’s findings in Nina’s blog.

It is rewarding to see the work we contributed to being part of a published international study. Even two years after the maps were produced, it is still deeply satisfying to be able to visualise the journeys of the Arctic Skuas when they are not on Rousay.

Since the Arctic Skua research programme was established in 2017, BTO donors have donated more than £225,000 to fund the work. We are enormously grateful for this very generous support from a small number of committed individuals. The research could not have been delivered without this funding. We would also like to thank the Scottish Ornithologists’ Club for annual grants that cover the cost of the productivity study on Rousay.

World Migratory Bird Day 2023

This blog post was created to celebrate World Migratory Bird Day (WMBD) 2023, a global event which increases the level of awareness about the threats that migratory birds are facing.

The theme of WMBD 2023 is Water, which highlights the importance of this resource for migrating birds – including for species like the Arctic Skua, which spends most of its life at sea and migrates thousands of kilometres over the ocean and across both hemispheres every year.

BTO’s Arctic Skua tracking project aims to understand where these birds spend their time when they’re not at their breeding colonies, so we can better inform global efforts to protect this species.

Share this page