Cuckoo

Cuculus canorus (Linnaeus, 1758)

CK

CUCKO

CUCKO  7240

7240

Family: Cuculiformes > Cuculidae

Cuckoo is a summer visitor to our shores, the males arriving in late April and leaving again as early as the first week of June.

Cuckoo numbers are declining in Britain, albeit with much regional variation, and the bird's familiar two-note call has been lost form many of its former haunts. It is the populations in the southern half of Britain that have undergone the greatest decline, something that has been linked to the different routes used by migrating Cuckoos as they travel to and from their African wintering grounds.

Since 2011, BTO researchers have been fitting tracking devices to Cuckoos breeding in Britain and elsewhere as part of the Cuckoo Tracking Project. This important research revealed the migration routes and wintering areas of British Cuckoos for the first time. While some birds migrate south-east via Italy, others take a western route. Interestingly, all of the birds winter in the same part of central Africa, and all of them return via the western route in spring. If you would like to support this ground-breaking research, please consider sponsoring a Cuckoo.

Exploring the trends for Cuckoo

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Cuckoo population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Cuckoo identification is usually straightforward. The following article may help when identifying Cuckoo.

Identifying Cuckoo

Cuckoos are well-known birds, but their distinctive and eagerly awaited song can be confused with several other species. Despite their popularity, Cuckoos are rarely seen and, when they are, can easily be mistaken for a bird of prey. Let us help you pick out this iconic bird that was once believed to turn into a Sparrowhawk in the winter - neatly explaining it's silence and disappearance outside the breeding season.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Cuckoo, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Song

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

The CBC/BBS trend shows Cuckoo abundance to have been in decline since the early 1980s. The species was moved in 2002 from the green to the amber list, and in the 2009 review met red-list criteria. The sensitivity of CBC to change in this species may have been relatively low, mainly because Cuckoo territories were typically larger than census plots (Marchant et al. 1990). BBS shows a continuing strong decline in England, but not in Scotland, where a moderate increase has occurred. In Wales, the species declined in the first 15 years of BBS but have been stable over the most recent ten year period. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that decrease has been most severe in Northern Ireland and southeastern England and that increase has occurred in northwestern Scotland. Cuckoos increased significantly during 1994-2006 in lowland semi-natural grass, heath and bog but decreased in almost all other habitat types (Newson et al. 2009). Results from analyses of data from two citizen science schemes, including BirdTrack, suggest regional differences in the UK may date back much earlier, with tentative comparisons made with data from 100 years ago (Sparks et al. 2017). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

| UK breeding population |

-35% decrease (1995–2022)

|

Exploring the trends for Cuckoo

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Cuckoo population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Breeding Cuckoos are found in over three-quarters of 10-km squares, in a range of habitat types, although they reach highest densities in upland and marginal habitats. Dartmoor, Exmoor and the New Forest in England, and the Brecon Beacons in Wales, hold relatively high densities but abundance peaks in western and northern Scotland and in western Ireland.

More from the Atlas Mapstore.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 2483 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 82 |

European Distribution Map

European Breeding Bird Atlas 2

Breeding Season Habitats

| Most frequent in |

Reedbed

|

Relative frequency by habitat

Relative occurrence in different habitat types during the breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

The Cuckoo’s British & Irish range contracted by 10% between 1968–72 and 1988–91.

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -8.2% |

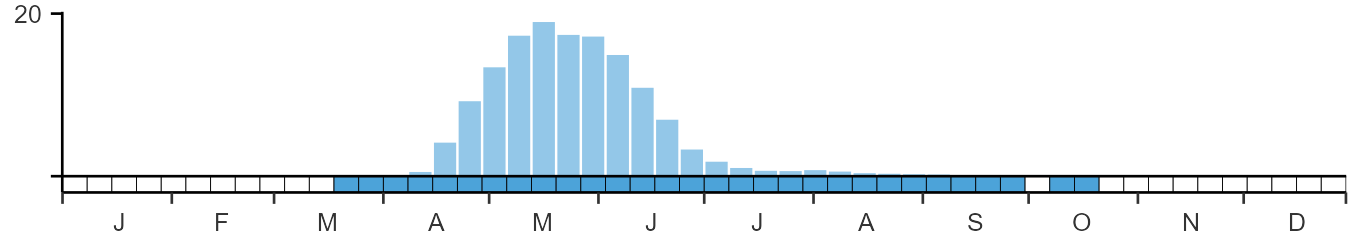

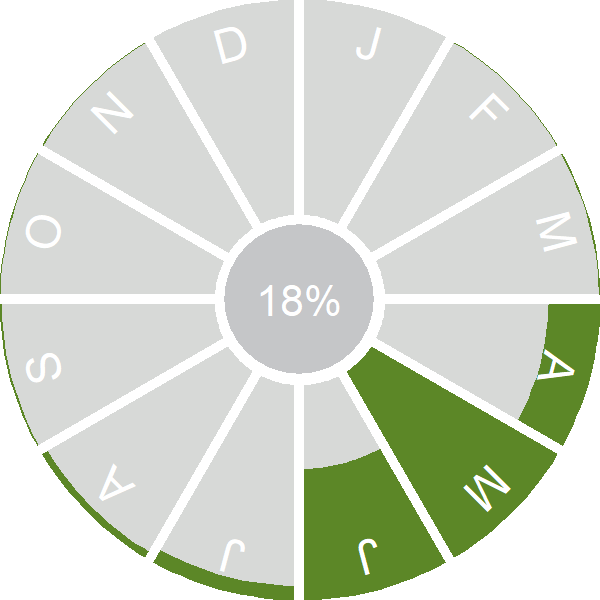

SEASONALITY

Cuckoos are summer visitors, arriving from mid-April with adults rapidly disappearing in June after egg laying, followed by a long tail of rarely-reported juveniles into early autumn.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Cuckoo, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Number of Broods

|

Jan–25 |

Egg Size

|

22×16 mm Weight = 3.2 g (of which 7% is shell) |

Exploring the trends for Cuckoo

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Cuckoo population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

6 years 11 months 2 days (set in 1983)

|

Exploring the trends for Cuckoo

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Cuckoo population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 218.2±8.1 | Range 207–232mm, N=144 |

| Juveniles | 198.8±13.9 | Range 169-218mm, N=105 | |

| Males | 222.3±7 | Range 210–234mm, N=85 | |

| Females | 211.9±5.2 | Range 204–221mm, N=52 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 114±15.7 | Range 93.0–143g, N=119 |

| Juveniles | 92.1±14.6 | Range 70.5–121g, N=99 | |

| Males | 120±13.8 | Range 98.0–143g, N=68 | |

| Females | 107±15.6 | Range 86.0–131g, N=46 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

D |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: CK | 5-letter code: CUCKO | Euring: 7240 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Cuckoo from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

Recent tracking work suggests that reduced survival on migration could be a primary driver of population decline in Cuckoos. However, this may not be the only driver and a number of other hypotheses have been proposed.

Further information on causes of change

Recent tracking work from nine tagging locations across the UK has identified that Cuckoos nesting in the UK use two distinct routes to reach the same wintering grounds, and identified a strong correlation between population trends in each area and the proportion of Cuckoos following each migration route. This suggests that recent problems on the western migration route through Spain may have contributed to the population decline (Hewson et al. 2016).

Decreased food supplies on the breeding grounds has also been suggested as a possible cause (Glue 2006, Denerley 2014), following the rapid declines of many British moth species (Conrad et al. 2006), important prey items in Cuckoo diet. Denerley et al. (2018) found that Cuckoo presence in Devon was related to that of macro-moth prey species, and suggested that the trends in prey species could explain the differing UK trends and also an increasing association with semi-natural sites such as heathland and wetland rather than lowland farm habitats. Based on both molecular DNA sequencing of faeces and the study of recent photos from crowd sourcing, Mills et al. (2020) concluded that Cuckoo diet was largely similar to that previously documented prior to the decline; they also surmise that this could explain the regional patterns of decline.

Given that the Cuckoo is a migrant, and the fact that many long-distance migrants have been found to be declining (Sanderson et al. 2006, Hewson & Noble 2009), factors operating on wintering grounds have also been suggested as a possible primary driver of Cuckoo declines (Glue 2006, Payevsky 2006, Newson et al. 2009). However, as trends differ across the UK, the fact that the tracking work ( Hewson et al. 2016) found that all Cuckoos used the same wintering grounds suggests that over-winter factors can be discounted.

Cuckoo abundance may be related to their breeding success, which might in turn be determined by the abundance of breeding success of host species. Evidence from BBS data show strong variation in Cuckoo population trends between habitats, which may reflect regional differences in the main hosts and differing trends in Cuckoo breeding success among those host species (Newson et al. 2009). Douglas et al. (2010b) found a strong positive correlation between change in Cuckoo numbers and numbers of Meadow Pipit in the previous year, also based on BBS data, but this only accounted for 1% of the decline in Cuckoo populations so this is unlikely to be a primary driver. A study from the 1980s using Nest Record Scheme data also found changes in usage of some key host species (Brooke & Davies 1987) but the authors also thought that this was unlikely to be the main cause of population decline. There has perhaps been a disproportionate emphasis on the role of brood parasitism aspects in Cuckoo decline.

Another hypothesis for the decline of Cuckoos relates to phenological mismatch in the timing of host and Cuckoo breeding. There is evidence relating to climate-induced changes in phenology. The extent to which this may be driving population declines is unclear, although modelling suggests that climate change may have had a negative impact on the long-term trend for this species (Pearce-Higgins & Crick 2019). Newson et al. (2016) found that Cuckoo had not changed its arrival date between the 1960s and the 2000s (the date advance slightly by c.3 days but this change was not significant). Douglas et al. (2010b) used BBS data and found that in recent decades, earlier breeding Dunnock nests have become less available to Cuckoos, whilst those of Reed Warblers more so. However, they suggested that changes in host phenology are likely to have had only a minimal impact on Cuckoo population trend (Douglas et al. 2010b). In Europe, other recent studies have suggested that climate change might disrupt the association between the life cycles of the Cuckoo and its short-distance migrant hosts and they state that this mismatch may contribute to the decline in Cuckoo (Saino et al. 2009, Moller et al. 2011). Thus, evidence at European scale at least is equivocal.

Information about conservation actions

The research suggests that reduced survival on the western migration route through Spain may be the primary driver of the population decline of the Cuckoo in the south and east of the UK (Hewson et al. 2016), and therefore conservation action outside the UK may be required to reverse the declines. However, there is also evidence suggesting that declines in prey species, in particular larger moths, may also have contributed to the declines (Denerley et al. 2018), and therefore actions to improve habitat to benefit invertebrates may also benefit this species. At a local level, these may include habitat actions such as the provision of beetle banks, set-aside, planting buffer strips around arable fields and restoring or creating semi-natural grassland.

However, Cuckoo territories are comparatively large and, if prey availability is contributing to the declines, it is likely that these will only be reversed if policies ensure that habitat management occurs over a correspondingly large scale through a landscape scale approach.

PUBLICATIONS (5)

Breeding ground correlates of the distribution and decline of the Common Cuckoo Cuculus canorus at two spatial scales

Cuckoos: England’s loss is Scotland’s gain

The Cuckoo is quickly declining from the English countryside, but this new study using BTO data shows that despite its decline in the south of the UK, it is increasing in the Scottish Highlands, the population is increasing.

Characteristics determining host suitability for a generalist parasite.

What makes a good host for a parasitic Cuckoo?

The Cuckoo is a generalist avian brood parasite, known to have utilized at least 125 different bird species as a host within Europe. Despite this, individual female Cuckoos are thought to be host-specific, preferentially laying their eggs in one – or a few – host nests. This raises the question of what makes a good host.

Flight Lines: Tracking the wonders of bird migration

By pairing artists, storytellers and photojournalists with the researchers and volunteers studying our summer migrants, we are able to tell the stories of our migrant birds, and the work being done

Population decline is linked to migration route in the Common Cuckoo, a long-distance nocturnally-migrating bird

Cuckoo declines linked to different migration routes to Africa

When the BTO began ground-breaking Cuckoo tracking research in 2011, we had very little idea where these birds spent the winter or how they got there. Our latest research not only reveals this information, but also shows that Cuckoos’ use of autumn migration routes helps explain population declines.

Spring arrival of the Common Cuckoo at breeding grounds is strongly determined by environmental conditions in tropical Africa

West African stopover determines timing of Cuckoo arrival

The authors use 11 years of satellite tracking data from 87 male Cuckoos, tagged at 11 sites across the UK, to examine variation in migratory timing throughout the annual cycle and its potential co

Links to more studies from ConservationEvidence.com

- The restoration of parasites, parasitoids, and pathogens to heathland communities

- Techniques for studying Maculinea butterflies: I. Rearing Maculinea caterpillars with Myrmica ants in the laboratory

- Observations on Phacelia tanacetifolia Bentham (Hydrophyllaceae) as a food plant for honey bees and bumble bees

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page