Curlew

Numenius arquata (Linnaeus, 1758)

CU

CURLE

CURLE  5410

5410

Family: Charadriiformes > Scolopacidae

Survey data have documented the decline in breeding Curlew populations across Britain & Ireland, prompting research and conservation efforts to support the species.

After decades of decline, particularly in farmland, Curlew are now a scarce breeding species in lowland areas, with strongholds in some upland landscapes. The bird's evocative bubbling call, echoing above the heather moorlands and upland-edge grazing, is a well-loved feature indicating the health of these important habitats.

In winter the population moves to the coasts and its adjacent farmland, where it is joined by large numbers of migrants from Fennoscandia. The Wetland Bird Survey records the two most important sites for Curlew as The Wash and Morecambe Bay, demonstrating its wide winter distribution.

Exploring the trends for Curlew

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Curlew population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Curlew identification is usually straightforward. The following article may help when identifying Curlew.

Identifying Curlew and Whimbrel

Curlew is a familiar wader, found in wild habitats around the UK. In April and May numbers of their smaller cousin, Whimbrel, will be moving through towards their northerly breeding sites and these birds can cause confusion. This video helps you to confidently separate the two species by sight and sound.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Curlew, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Alarm call

Call

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

CBC and BBS reveal a long-term decline, despite an initial increase that lasted until the mid 1970s. At WBS/WBBS sites, in contrast, the downturn did not begin until the late 1990s, suggesting there may have been some movement during the 1980s and 1990s from farmland onto wetter sites. Surveys of lowland wet grassland, however, showed Curlew losses of almost 39% between 1982 and 2002, more specifically of 34% in England and 75% in Wales (Wilson et al. 2004, 2005a). Breeding Curlews had declined significantly between 1980 and 2002 in six of 13 upland study areas across Britain (Sim et al. 2005). A 2006 survey in Wales highlighted the rapid decline of the species across all habitats, with low breeding success as a plausible mechanism (Johnstone et al. 2007). In Northern Ireland, the breeding population had shrunk to just 526 (252-783) pairs by 2013, representing a decrease of around 82% since 1987, with the distribution becoming increasingly fragmented (Colhoun et al. 2015). Through its UK breeding decline, the species moved from amber to being red listed in the latest review (Eaton et al. 2015).

BBS trends show continued declines since 1995 throughout the UK, with the strongest declines in Scotland and in Wales. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that decrease has been concentrated into southwestern Scotland, Wales and parts of northern England, with increases in a few regions of Cumbria and the Pennines. Wintering Curlew abundance showed a shallow long-term increase to around 2000, but has since declined (WeBS: Frost et al. 2020). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>). Through its Near Threatened global status and the international importance of the declining UK populations, and bearing in mind the history of extinction and declines among its close relatives (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2017), Curlew has been identified by one paper as 'the most pressing bird conservation priority in the UK' (Brown et al. 2015).

| UK breeding population |

-50% decrease (1995–2022)

|

| UK winter population |

-32% decrease (1996/97–2021/22)  |

Exploring the trends for Curlew

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Curlew population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Although Curlews still breed in many areas of northern and western Britain, particularly uplands and marginal areas, but the range is significantly smaller than it used to be and abundance has decreased almost everywhere. Further south and east there are isolated small populations, such as in the Brecks of East Anglia. Losses in Ireland have been extreme. In winter, UK breeding Curlews move to the coast and adjacent farmland, where they are joined by large numbers of migrants from Fennoscandia. Highest densities are on the major estuaries, the Northern Isles and in western Ireland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 1692 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 56 |

| No. occupied in winter | 1767 |

| % occupied in winter | 59 |

European Distribution Map

European Breeding Bird Atlas 2

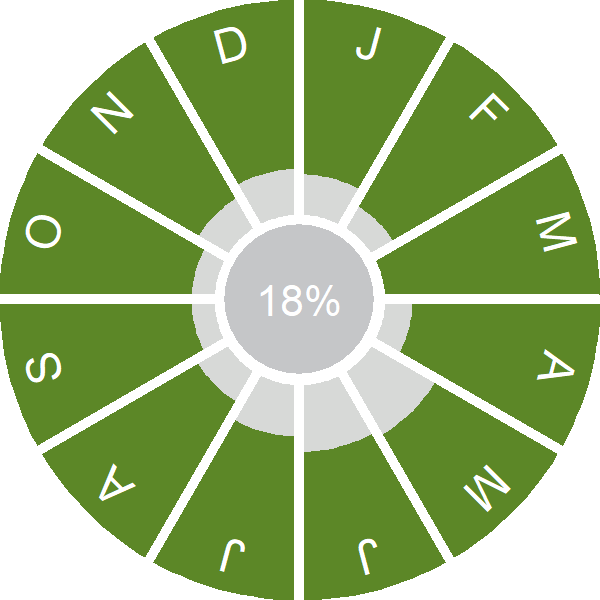

Breeding Season Habitats

| Most frequent in |

Moorland

|

| Also common in | Marsh |

Relative frequency by habitat

Relative occurrence in different habitat types during the breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

The loss of breeding Curlews from most of Ireland and parts of western Britain over the last 40 years is a major conservation issue. Since the 1968–72 Breeding Atlas the range has contracted by 78% in Ireland and 17% in Britain. In Ireland losses have occurred mostly within the last 20 years.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -19.2% |

| % change in range in winter (1981–84 to 2007–11) | +11.6% |

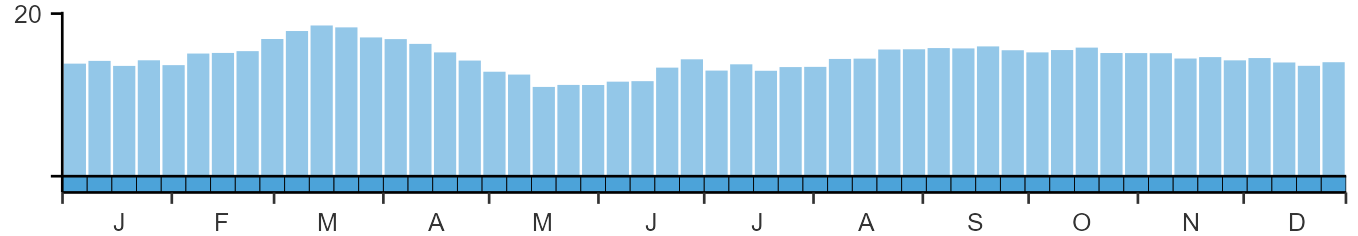

SEASONALITY

Curlews are recorded throughout the year.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Curlew, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

First Clutches Laid

|

2 May (17 Apr–31 May)

|

Number of Broods

|

1 |

Egg Size

|

68×48 mm Weight = 76 g (of which 6% is shell) |

Clutch Size

|

4 eggs | 3.72 ± 0.58 (2–6) N=827

|

Exploring the trends for Curlew

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Curlew population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

32 years 7 months 0 days (set in 2011)

|

Typical Lifespan

|

11 years with breeding typically at 2 year |

Adult Survival

|

0.899±0.01

|

Juvenile Survival

|

0.47 (in first year)

|

Exploring the trends for Curlew

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Curlew population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 306±11 | Range 289–324mm, N=1696 |

| Juveniles | 295.2±13 | Range 277-315mm, N=182 | |

| Males | 295.1±10.6 | Range 280–310mm, N=95 | |

| Females | 310.3±10 | Range 290–325mm, N=96 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 823±106.6 | Range 660–1000g, N=1600 |

| Juveniles | 725±108.1 | Range 550–900g, N=143 | |

| Males | 716±68 | Range 632–842g, N=66 | |

| Females | 852±89 | Range 710–985g, N=62 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

F |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: CU | 5-letter code: CURLE | Euring: 5410 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Curlew from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

There is good evidence that loss of habitat is the main cause of decline of Curlew. Decline of the species on grassland is likely to be correlated to draining of fields, whilst predation is likely to be important at a site level. The decline of Curlew recorded by WBS/WBBS may be related to other causes, such as land reclamation but data are not available. The conservation of Curlew is likely to benefit from wader-friendly management of land, including restoration of ditches, wet features within fields and heterogeneous vegetation. Further studies should concentrate on investigating the direct link between Curlew abundance and management of coastal areas, including the outcome of displacement of individuals from feeding sites on mudflats.

Further information on causes of change

Analysis investigating potential drivers of breeding abundance and population change across Britain, using BBS data from 1995-99 and 2007-11, found support for the negative effects of intensive agriculture, forestry, increased predation and climate warming on Curlew abundance and population trends, and suggested that site protection, measures to reduce generalist predator abundance and wider improvements to breeding habitat may be required to reverse declines (Franks et al. 2017).

Habitat change is the main cause of decline that has been identified by other studies, in particular drainage of grassland and management changes in the uplands. Loss of peatland, drainage of wetlands and afforestation have been suggested as causes of decline in Ireland (Partridge & Smith 1992). In a Northern Irish study, the preferred habitat for Curlew was bog/mire and unimproved grassland, with areas of standing water, whilst the species was less abundant than expected on improved grassland, upland rough grassland and arable land (Henderson et al. 2002). In the Welsh uplands, abundance was highest in moorland edge habitats with both moorland and improved grassland, and success was associated with mire habitats with Trichophorum germanicum (Johnstone et al. 2017). In a study of GPS tracked birds in Scotland, two birds travelled at night to improved grassland up to 1.6km away from the nest site, presumably to forage, but a third bird stayed close to the nest and apparently did not use improved grassland, suggesting that habitat usage may be variable (Ewing et al. 2017).

Amar et al. (2011) showed that, between 1980-93 and 2000-02, Curlews had declined most in heather-dominated upland sites and least in bog-dominated ones. An earlier study had found that Curlew abundance was higher on moorland managed for grouse shooting than on other moorland, probably mediated by increased predator control on grouse moors (Tharme et al. 2001): these results led to the suggestion that reduction in grouse moor, managed to favour heather regrowth and to control predators, might be behind the decline of wader populations in the uplands (Baines et al. 2008, Fletcher et al. 2010), but Amar et al. (2011) found no correlation between grouse moor and Curlew population change. Recent studies of upland moorland management have suggested that vegetation heterogeneity and structural complexity are important for Curlews (Buchanan et al. 2017) and abundance increased in a study in Cumbria when a greater area of vegetation was cut (Douglas et al.2017).

Studies of the impact of predators on Curlew abundance and breeding success have reached opposing conclusions, suggesting some case-by-case relevance of predators to local Curlew populations. A study on upland waders found no negative spatial or temporal relationship between Ravens and Curlew abundance, using surveys from 1980 and 1993 repeated in 2000 and 2002 (Amar et al. 2010b). In contrast, control of foxes and crows on two moorland and marginal farmland plots in Northumberland increased breeding success from 15% to 50%, with an increase of 14% per annum in breeding numbers after a three-year lag (Fletcher et al. 2010), and a study covering four upland regions found a positive correlation between predator control and Curlew abundance (Buchanan et al. 2017). Predation of eggs was identified as the primary proximate cause of failure in up to 97% of nests in a study during 1993-95 in Northern Ireland (Grant et al. 1999), and a study in Breckland in 2017-18 also recorded low and unsustainable nest survival rates, mainly due to predation by foxes (Zielonka et al. 2019). Increases in Curlew numbers at Langholm Moor between 2008 and 2017 were also attributed to predator control (Ludwig et al. 2019). A survey of 18 estates in northern England and south-east Scotland also concluded that predator control had positive effects on Curlew abundance, but found that these effects saturate at a relatively low level of control above which there were few benefits (Littlewood et al. 2019). On Shetland however, no evidence was found of a relationship between Curlew and predator abundance over 40 farms participating in the Agri-Environment Scheme (AES) (van der Wal & Palmer 2008). In Sweden, Curlew nest predation rates were higher in mixed farm landscapes than in arable ones (Berg 1992). A study on mixed farmland in Perthshire, however, crop type changes were identified as a likely contributor to declines over 1990-2015, though mammalian predators were not monitored (Bell & Calladine 2017).

Curlews are expected to respond adversely to climate change (Renwick et al. 2012, Douglas et al. 2014). It has been suggested that Curlews and other breeding waders are becoming increasingly restricted to sites managed as nature reserve or under the higher tiers of AES (Ausden & Hirons 2002, Wilson et al. 2004, 2007, O'Brien & Wilson 2011). Some authors have found potential benefits of AES for Curlews and other waders, e.g. where stocking densities have been reduced (van der Wal & Palmer 2008), but others have found that the benefits of AES are not always apparent or do not apply to all wader species (O'Brien & Wilson 2011, Smart et al. 2013). Nevertheless, conservation of Curlew is likely to benefit from wader-friendly management of land, including restoration of ditches, of wet features within fields and of vegetation diversity.

An expert assessment of global threats to Curlew and its near relatives (Pearce-Higgins et al. 2017) identified agricultural and land-use changes (crops, livestock and plantations), dams, drainage, invasive species and climate change as the threats most likely to have had the greatest breeding season impact on population trends within the East Atlantic flyway (which includes the British Isles). Outside the breeding season, they considered that the main threats came from agriculture (crops), aquaculture and fishing, renewable energy, transport, disturbance, drainage and climate change.

A study of colour-ringed birds wintering in south-west England suggested that apparent survival was highest during winter, and hence the main threats to this wintering population appeared to be during the breeding season or on migration (Robinson et al. 2020)

Information about conservation actions

The main cause of the decline is believed to relate to habitat changes at breeding sites (see Causes of Change section, above), and therefore improvements to breeding habitat may be required to halt and reverse declines. The conservation of Curlew at a local scale is likely to benefit from wader-friendly management of land, including restoration of ditches, wet features within fields and heterogeneous vegetation, and delaying cutting of fields. Predation may be important at some sites (see Causes of Change section) and therefore measures to control and reduce generalist predator abundance may also benefit the species (Franks et al. 2017). However, a survey of 18 estates in northern England and south-east Scotland found that the positive effects of predator control on Curlew abundance saturate at a relatively low level of control above which there were few benefits (Littlewood et al. 2019). The same study did not find any benefits to waders resulting from heather burning.

In Ireland, a participatory approach involving communication and involvement of all stakeholders is being used to attempt to reverse the decline; whilst early results appear to be encouraging, ongoing stakeholder collaboration and government support may be needed to maintain a viable breeding population (Young et al. 2020).

At a national scale, the provision of options to enable local habitat management actions may help increase the take up of habitat management options to benefit Curlews. A Swedish study found that breeding populations increased most at sites with the greatest proportion of grassland suggesting that this habitat if important for Curlews (Berg 1994). A study in Breckland found that Curlew selected experimentally physically disturbed grassland plots rather than undisturbed grassland for nesting, and suggested that undertaking ground disturbance, e.g. through shallow-cultivating, could be used to attract Curlew to safer areas to nest, such as inside anti-predator fences (Zielonka et al. 2019). Habitat management in Wales to provide a mosaic of short and taller moorland vegetation, new pools and enclosed grassland was successful in increasing breeding populations but the effect was short-lived (Fisher & Walker 2015).

PUBLICATIONS (14)

Assessing drivers of winter abundance change in Eurasian Curlews Numenius arquata in England and Wales

Consequences of population change for local abundance and site occupancy of wintering waterbirds

Wavering Waterbirds

Protected sites are assigned based on population statistics for vulnerable and endangered species. This new study using WeBS data shows that changes in population size can affect local abundance, and thus influence whether or not key targets are met for site protection.

Contrasting habitat use between and within Bar-tailed Godwit and Curlew wintering on the Wash, England

Adjacent habitats vital for intertidal waders

A new study has revealed contrasting habitat use between and within Bar-tailed Godwits and Curlews wintering on the Wash.

Curves for Curlew: Identifying Curlew breeding status from GPS tracking data

Tracking data allows researchers to monitor Curlew without disturbance during the breeding season

The Curlew is of significant conservation concern in the UK, but many questions still remain about their breeding behaviour.

Environmental correlates of breeding abundance and population change of Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata in Britain

The decline of the Curlew

Wader populations are declining worldwide, and here in the UK we have seen dramatic declines of Curlew populations. This study by the BTO in cooperation with the RSPB looks at which threats are influencing our Curlew.

Individual, sexual and temporal variation in the winter home range sizes of GPS-tagged Eurasian Curlew Numenius arquata

Curlew are highly faithful to a small winter range, a finding which will inform conservation management for this Red-listed species.

In a collaborative study led by the University of Hull, BTO scientists aimed to find out more by establishing the overwinter home range size (the size of the space used by the birds during winter)

Links to more studies from ConservationEvidence.com

- Habitat restoration for curlew Numenius arquata at the Lake Vyrnwy reserve, Wales

- An example of a two-tiered agri-environment scheme designed to deliver effectively the ecological requirements of both localised and widespread bird species in England

- Susceptibility of Bush Stone-curlews (Burhinus grallarius) to sodium fluoroacetate (1080) poisoning

Would you like to search for another species?

Help us collect data and improve this page for Curlew

Breeding Waders of Wet Meadows

Help us monitor the long-term population changes of our lowland breeding waders in England and Wales.

Join Breeding Waders of Wet Meadows today

Share this page