Tree Sparrow

Passer montanus (Linnaeus, 1758)

TS

TRESP

TRESP  15980

15980

Family: Passeriformes > Passeridae

Slightly smaller that the much commoner House Sparrow, the Tree Sparrow’s chestnut crown and black spot in the white cheek make it easy to identify.

Very much a bird of farmland edge, the UK Tree Sparrow population declined dramatically in the 1980s. Recent data, however, show small signs of recovery, although this species remains on the the UK Red List, where it has been found since 1996.

Tree Sparrows are found primarily in eastern and lowland areas of Britain & Ireland. East Yorkshire is a stronghold for British Tree Sparrows, and they can be locally common during the April to August breeding season. Outside of this time Tree Sparrows can move quite some distance with some breeding areas being vacated altogether. Some of the East Yorkshire birds have been reported during the winter months in Suffolk, heading back north as winter turns to spring. Where breeding, Tree Sparrows can be found in small, loose colonies.

Exploring the trends for Tree Sparrow

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Tree Sparrow population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Tree Sparrow identification is often straightforward. The following article may help when identifying Tree Sparrow.

Identifying common sparrows & Reed Bunting

Sparrows are not just sparrows - are they House Sparrows or Tree Sparrows? In winter, the familiar sparrows in your garden may be joined by an unfamiliar brown bird, the Reed Bunting. Let us help you to tell these three brown garden birds apart.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Tree Sparrow, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Call

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

Tree Sparrow abundance nose-dived spectacularly in the UK between the late 1970s and the early 1990s. BBS data indicate a significant increase since 1995, but it should be remembered that, for every Tree Sparrow today there were perhaps around 20 in the 1970s, and any recovery therefore has a very long way to go. Clear range contractions occurred between the first two breeding atlas periods (Gibbons et al. 1993), and have accelerated subsequently: Tree Sparrows have now withdrawn completely from some southern and western regions of Britain, but conversely have spread in Northern Ireland (Balmer et al. 2013). Following declines across western and northwestern Europe during the 1990s, the European status of this species is no longer considered 'secure' (BirdLife International 2004). There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>).

| UK breeding population |

+62% increase (1995–2022)

|

Exploring the trends for Tree Sparrow

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Tree Sparrow population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Following major changes in distribution since the 1970s, Tree Sparrows are now concentrated in low-lying parts of central and northern England, in eastern Scotland, the Welsh Marches, and around Lough Neagh and in eastern Irish counties. In both seasons, densities are highest in northeast England and Scotland.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 1079 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 36 |

| No. occupied in winter | 1244 |

| % occupied in winter | 41 |

European Distribution Map

European Breeding Bird Atlas 2

Breeding Season Habitats

| Most frequent in |

Arable Farmland

|

Relative frequency by habitat

Relative occurrence in different habitat types during the breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

Trends differ markedly across Britain and Ireland. In Ireland there has been a 71% winter range expansion since the 1980s. In contrast, the British range has contracted by 20% in winter since 1981–84 and by 41% in the breeding season since 1968–72. Tree Sparrows have disappeared from much of southeast England, south Wales, the Pennines and the western part of the Central Belt in Scotland. These losses are offset slightly by gains in northeast Scotland.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | -37.3% |

| % change in range in winter (1981–84 to 2007–11) | --17.5% |

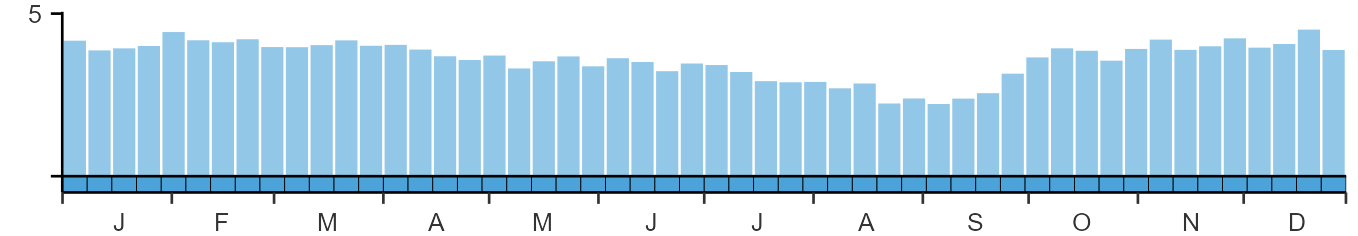

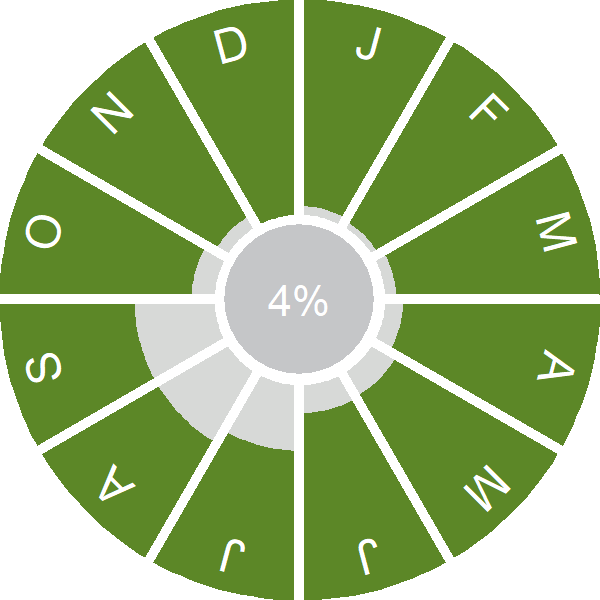

SEASONALITY

Tree Sparrow is recorded throughout the year on up to 5% of complete lists.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Tree Sparrow, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Exploring the trends for Tree Sparrow

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Tree Sparrow population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

10 years 10 months 20 days (set in 1996)

|

Typical Lifespan

|

2 years with breeding typically at 1 year |

Adult Survival

|

0.433±0.067

|

Exploring the trends for Tree Sparrow

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Tree Sparrow population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 69.6±2 | Range 67–73mm, N=5335 |

| Juveniles | 66.3±2.2 | Range 63-70mm, N=226 | |

| Males | 70.4±1.7 | Range 67–73mm, N=169 | |

| Females | 68.4±1.9 | Range 66–72mm, N=267 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 21.0±1.3 | Range 19.0–23.3g, N=4538 |

| Juveniles | 20.0±1.8 | Range 17.0–22.9g, N=166 | |

| Males | 21.3±1.6 | Range 19.0–23.2g, N=149 | |

| Females | 21.7±1.8 | Range 19.1–24.9g, N=195 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

A (pulli B) |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: TS | 5-letter code: TRESP | Euring: 15980 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Tree Sparrow from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

The mechanisms underlying the decline in this species are largely unknown, although demographic trends suggest that factors operating during the breeding season are not the main driver.

Further information on causes of change

The number of fledglings per breeding attempt has improved substantially as population sizes have decreased (see above), suggesting that decreases in productivity were not responsible for the decline. This has been driven by declines in daily failure rate at both the nest and chick stages and increases in clutch and brood sizes. It is thus more likely that survival has been the critical demographic measure, although ring-recovery analyses have produced equivocal results, perhaps because of small sample sizes (Siriwardena et al. 1998, 2000b).

Components of agricultural intensification, such as reductions in winter stubble, have been implicated in the decline, although direct evidence supporting such ideas is largely incidental. Tree Sparrows aggregate in areas where seed food is available during the winter and they have declined at the same time as other farmland seed-eaters (Siriwardena et al. 1998), providing circumstantial evidence for shortage of food. In winter in Scotland (Hancock & Wilson 2003), the highest densities of Tree Sparrows were recorded in cereal stubble fields (undersown with grass) and weedy brassica fodder crops. These habitats remain relatively seed-rich but have declined in area in the UK (Fuller 2000, Hancock & Wilson 2003). Field & Anderson (2004) also state that anecdotal evidence suggests that many Tree Sparrow colonies are strongly associated with winter seed food sources, and provision of new seed sources is frequently associated with the establishment of new breeding colonies. Although Siriwardena et al. (2007) did not find a significant positive relationship between winter food supply and breeding population trajectory in areas provisioned by RSPB Bird Aid, this may be due to the fact that the BBS trends for this species are increasing; therefore winter food may not currently be limiting, as the remaining populations are in small remnants of suitable habitat and many are subject to active conservation action (e.g. provision of nest boxes). In Northern Ireland, Colhoun et al. (2017) observed an increase in abundance over five years on farms participating in agri-environment schemes, but found no direct positive association with the provision of seed rich habitat or any other specific management options.

During the breeding season, Field & Anderson (2004) found that wetland-edge habitats played a key role in providing invertebrate prey to allow successful chick rearing throughout the long breeding season and suggest that it is possible that large areas of UK farmland that were formerly occupied no longer provide these invertebrate resources, due to the effects of intensification in the late 20th century. In a study in Wiltshire, McHugh et al. (2016a) examined faecal sacs from nestlings and found a higher proportion of seed in their diet in areas with wild bird seed cover planted to provide seed resources in winter. They surmised that this indicated a shortage of insects, which are a more suitable nestling food. In this study, colony size increased but breeding success decreased in areas with wild bird seed cover (McHugh et al. 2017)

Information about conservation actions

The main drivers of change for the Tree Sparrow are uncertain, but it is believed most likely that declines have been caused by changes in survival. Therefore actions and agri-environment policies to increase seed food availability over winter could potentially benefit this species. However, Siriwadena et al. (2007) did not find a significant positive relationship between winter food supply and trends in a UK-wide study, possibly indicating that winter food may not currently be limiting as the remaining populations are in small remnants of suitable habitat and many are already subject to active conservation action (e.g. provision of nest boxes).

Providing overwinter food using wild bird seed cover may also have unintended negative impacts on breeding performance, with nestlings being fed on larger quantities of seed and experiencing reduced fledging success (McHugh et al. 2016a, 2017). This is likely to reflect a shortage of invertebrates and therefore actions to address this shortage may be at least as important in some areas as providing overwinter food. These actions could include using existing agri-environment options to provide habitats which support key invertebrate prey items used by Tree Sparrows during the breeding season (Field et al. 2010). Wetland-edges are a key habitat which help provide invertebrates and hence may help improve Tree Sparrow productivity (Field & Anderson 2004).

Further actions which encourage Tree Sparrows to return to sites from which they have been lost due to agricultural intensification are also likely to be required in order to enable a full recovery to take place. As well as providing nest boxes at sites close to existing populations (e.g. von Post et al. 2015), local conservation actions and agri-environment options will be needed to ensure that invertebrate prey are available at these sites during the breeding season and that seeds are available over winter.

PUBLICATIONS (1)

Drivers of the changing abundance of European birds at two spatial scales

Study highlights significant losses of European birds

This piece of research explores the question of measuring and detecting biodiversity change for European birds, which are well monitored in many European countries thanks to ongoing monitoring prog

Links to more studies from ConservationEvidence.com

- Habitat use by breeding tree sparrows Passer montanus

- Evaluating the English Higher Level Stewardship scheme for farmland birds

- Does variation in garden characteristics influence the conservation of birds in suburbia?

Read more studies about Tree Sparrow on Conservation Evidence >

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page