Willow Warbler

Phylloscopus trochilus (Linnaeus, 1758)

WW

WILWA

WILWA  13120

13120

Family: Passeriformes > Phylloscopidae

A member of the leaf warbler family, the beautiful olive and yellow Willow Warbler is also one of our most widespread.

A summer visitor to the Britain & Ireland, the Willow Warbler’s cascading, liquid song can be heard from mid-April and is arguably one of the most beautiful sounds of the spring. Willow Warblers can be found breeding across Britain & Ireland.

The Willow Warbler population has experienced mixed fortunes in the UK, where it is Amber-listed. It is declining across England and Wales but increasing in Scotland and Northern Ireland. It is thought that the northern populations winter in a slightly different area from the southern birds and that this difference might contribute to the overall UK trend.

Exploring the trends for Willow Warbler

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Willow Warbler population is changing.

trends explorerIdentification

Willow Warbler identification is sometimes difficult. The following article may help when identifying Willow Warbler.

SONGS AND CALLS

Listen to example recordings of the main vocalisations of Willow Warbler, provided by xeno-canto contributors.

Call

Song

Develop your bird ID skills with our training courses

Our interactive online courses are a great way to develop your bird identification skills, whether you're new to the hobby or a competent birder looking to hone your abilities.

Browse training coursesStatus and Trends

Population size and trends and patterns of distribution based on BTO surveys and atlases with data collected by BTO volunteers.

CONSERVATION STATUS

This species can be found on the following statutory and conservation listings and schedules.

POPULATION CHANGE

Willow Warbler abundance has shown regionally different trends within the UK (Morrison et al. 2010, 2013a, 2015, 2016c, Massimino et al. 2013, Balmer et al. 2013). The overall CBC/BBS trend shows a rapid decline during the 1980s and early 1990s, after 20 years of relative stability, and, on the strength of a 31% decline on CBC plots between 1974 and 1999, the species was moved from the green to the amber list. This decline occurred mainly in southern Britain, however, accompanied by a fall in survival rates there (Peach et al. 1995a), with Scottish populations remaining unaffected. The differing regional trends have been linked to differences in productivity (Morrison et al. 2016c). BBS figures indicate a contrast between an upward trend in Scotland and in Northern Ireland since 1995, and continued severe decreases in England, with no overall trend in Wales. The BBS map of change in relative density between 1994-96 and 2007-09 indicates that strong decrease was widespread across England and Wales over that period, with little change across Northern Ireland, northern England and most of Scotland and increases in the far northwest. However, the most recent 5-year BBS trends suggest that declines are now occurring in Northern Ireland and that the previously increasing trend in Scotland may now have levelled off.

There has been a decline across Europe since 1980 (PECBMS: PECBMS 2020a>; see also Lehikoinen et al. 2014).

| UK breeding population |

-9% decrease (1995–2022)

|

Exploring the trends for Willow Warbler

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Willow Warbler population is changing.

trends explorerDISTRIBUTION

Willow Warbler are widespread with gaps restricted to a few 10-km squares around the Fens in eastern England and to the Outer Hebrides and Northern Isles. Densities are low in much of southern, central and eastern England, and at higher altitudes in the Scottish Highlands. They are greatest in the northern half of Ireland, Wales, much of northern England and southern Scotland, together with the foothills and glens of the Scottish Highlands.

Occupied 10-km squares in UK

| No. occupied in breeding season | 2831 |

| % occupied in breeding season | 94 |

| No. occupied in winter | 29 |

| % occupied in winter | 1 |

European Distribution Map

European Breeding Bird Atlas 2

Breeding Season Habitats

| Most frequent in |

Scrub

|

| Also common in | Coniferous Wood |

Relative frequency by habitat

Relative occurrence in different habitat types during the breeding season.

DISTRIBUTION CHANGE

Although there has been a small range expansion, the most striking change is the polarised pattern of relative abundance change, with Willow Warblers apparently increasing in Scotland and Wales but declining across much of England.

Change in occupied 10-km squares in the UK

| % change in range in breeding season (1968–72 to 2008–11) | +2.7% |

| % change in range in winter (1981–84 to 2007–11) | +40% |

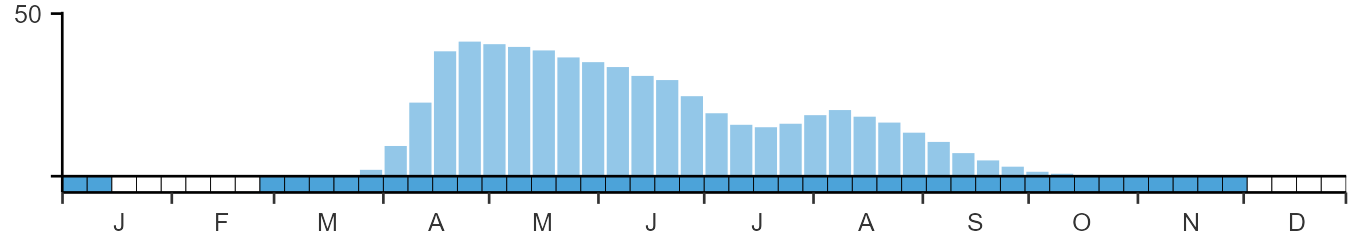

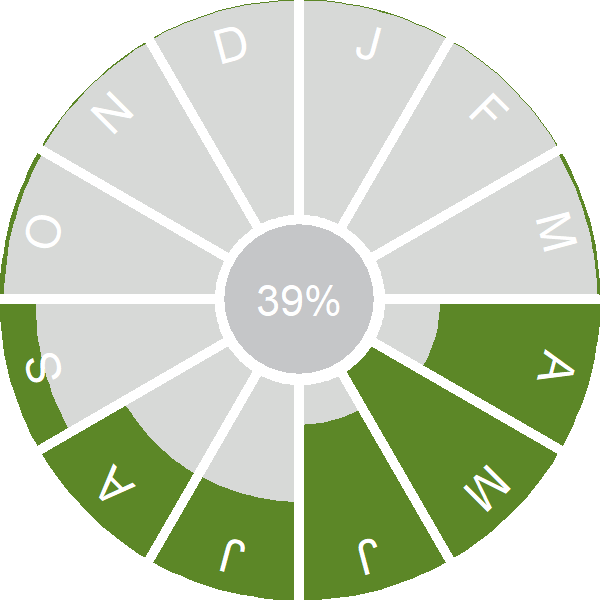

SEASONALITY

Willow Warbler is a summer migrant, arriving from April with an early return passage during August and September.

Movement

Information about movement and migration based on online bird portals (e.g. BirdTrack), Ringing schemes and tracking studies.

An overview of year-round movements for the whole of Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

RINGING RECOVERIES

View a summary of recoveries in the Online Ringing Report.

Foreign locations of birds ringed or recovered in Britain & Ireland

Biology

Lifecycle and body size information about Willow Warbler, including statistics on nesting, eggs and lifespan based on BTO ringing and nest recording data.

PRODUCTIVITY & NESTING

Exploring the trends for Willow Warbler

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Willow Warbler population is changing.

trends explorerSURVIVAL & LONGEVITY

View number ringed each year in the Online Ringing Report

Maximum Age from Ringing

|

10 years 11 months 18 days (set in 2010)

|

Typical Lifespan

|

2 years with breeding typically at 1 year |

Adult Survival

|

0.46±0.07

|

Juvenile Survival

|

0.239 (in first year)

|

Exploring the trends for Willow Warbler

Our Trends Explorer will also give you the latest insight into how the UK's Willow Warbler population is changing.

trends explorerBIOMETRICS

Wing Length

|

Adults | 66.3±4.4 | Range 62–71mm, N=35993 |

| Juveniles | 64.8±2.8 | Range 61-69mm, N=41601 | |

| Males | 68.9±5.7 | Range 66–71mm, N=11930 | |

| Females | 63.2±1.6 | Range 61–65mm, N=7344 |

Body Weight

|

Adults | 8.90±0.9 | Range 7.50–10.4g, N=31141 |

| Juveniles | 8.70±1.2 | Range 7.40–10.2g, N=33348 | |

| Males | 9.30±0.7 | Range 8.20–10.5g, N=9756 | |

| Females | 8.50±0.9 | Range 7.40–10.2g, N=6217 |

Feather measurements and photos on featherbase

CODES & CLASSIFICATION

Ring size

|

AA |

Field Codes

|

2-letter: WW | 5-letter code: WILWA | Euring: 13120 |

For information in another language (where available) click on a linked name

Research

Interpretation and scientific publications about Willow Warbler from BTO scientists.

CAUSES AND SOLUTIONS

Causes of change

The causes of decline are uncertain. Decreased breeding success is likely to be an important driver of the decline in the south-east, and the differing trends across the UK suggest that climate change (or possibly habitat changes occurring over wide areas) could be a factor behind the changes. However, problems on migration or in winter have not been completely ruled out.

Further information on causes of change

Willow warbler is among a suite of species that winter in the humid zone of West Africa and correspondingly are showing the strongest population declines among our migrant species (Ockendon et al. 2012, 2014). Pressures on migration and in the winter are likely to be affecting the population, as is a reduction in habitat quality on the breeding grounds (Fuller et al. 2005). A study based on BBS results from 1995 to 2006 found a negative correlation between the abundance of deer and Willow Warbler, with the species declining the most where deer population increase had been greatest, although the size of the impact was relatively small with modelling suggesting that deer could have caused a decline of around 4% over this period (Newson et al. 2012).

The decline in the south in the early 1990s has previously been linked to reduced adult survival (Peach et al. 1995a). However, more recent analysis of annual population changes and winter survival estimates across western Europe shows only a weak relationship between survival and population change, suggesting than long-term population change may be mostly driven by reduced productivity or juvenile survival ( Johnston et al. 2016). This is supported by CES results: the recent population decline is associated with a decline in productivity as measured by CES and with a substantial increase in nest failure rates. There is also a small but significant decrease in the number of fledglings per breeding attempt. Average laying dates have shifted earlier by a week, perhaps in response to recent climatic warming (Crick & Sparks 1999). In the southeast, the seasonal decline in productivity has strengthened and, despite the advance in timing of breeding, overall productivity has declined, whereas overall productivity has been stable in the northwest (Morrison et al. 2015). Although annual productivity rates and survival are variable across the UK, regional integrated population models showed that high annual productivity during 1994-2012 sometimes coincided with high survival in the north-west of Britain, leading to population growth, but high productivity is rarer in the south-east and never coincided with high survival (Morrison et al. 2016c).

There is also evidence that sex ratios vary across Britain and have become male-biased in many areas of low abundance such as south-east England, which may affect local productivity (Morrison et al. 2016b).

Information about conservation actions

The decline of this species in the UK has been driven by rapid declines in the south and east of England which contrasts with increases in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Conservation actions to reverse the declines therefore need to focus on identifying and addressing the problems in the south-east whilst maintaining conditions further north and west.

If these problems are caused by issues occurring during the breeding season rather than at other times, they could be linked to climate change or possibly to widespread habitat changes; therefore conservation actions in the south-east should focus on creating and maintaining good quality breeding habitat for Willow Warblers in order to help mitigate some of the effects of climate change (Mallord et al. 2016c).

Restoring or creating forests can help provide such habitat. Research suggests that Willow Warblers prefer woods with mean vegetation heights (3.7-5.3 m) and that these need to be relatively large (>0.5 ha) (Bellamy et al. 2009). The same study found that woodland that was 6-11 m high appeared less suitable and therefore rotational woodland management techniques which ensure that early successional patches continue to be available are most likely to retain Willow Warblers. Control of deer abundance within managed woodlands could possibly also benefit Willow Warblers (Newson et al. 2012; see Causes of Change section, above).

In addition to the woodland management activities described (and policies to encourage such activities), decisions about infrastructure projects can potentially have effects on Willow Warblers which extend some distance beyond the boundary of the project itself. A Dutch study found lower densities breeding in areas with apparently suitable habitat within 200 m of highways, and breeding productivity was also lower in those areas, which were occupied later in the season (Reijnen & Foppen 1994).

PUBLICATIONS (5)

Breeding ground temperature rises, more than habitat change, are associated with spatially variable population trends in two species of migratory bird

A tale of two warblers

Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) results show very different population trends for Willow Warbler and Chiffchaff - but what is driving this difference? BTO research reveals climate is key.

Causes and consequences of spatial variation in sex ratios in declining bird species

Causes and consequences of spatial variation in Willow Warbler sex ratios

New BTO research shows a recent imbalance in Willow Warbler sex ratios, with 60% of adult birds being male. Such a skewed ratio has implications for the conservation of this migrant species.

Demographic drivers of decline and recovery in an Afro-Palaearctic migratory bird population

Why are Willow Warblers decreasing in the south, but not the north?

New research involving the BTO suggests that Willow Warbler population declines in southern Britain might be reversed by improving productivity there.

Differential changes in life cycle-event phenology provide a window into regional population declines

Research reveals why Willow Warblers breeding in different parts of Britain are affected by climate change in different ways.

Using stable isotopes to link breeding population trends to winter ecology in Willow Warblers Phylloscopus trochilus

Willow Warbler breeding trends linked to winter ecology

Like many Afro-Palaearctic migrants, Willow Warbler numbers have fallen in the UK in recent decades. However, these declines vary regionally, with marked losses in the south and east of England, but smaller decreases, or even increases, in the north and west of England and Scotland. Could these contrasting population trends be explained by differences in the conditions birds experience outside of the UK? New research by the BTO, the University of East Anglia and the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre has used stable isotope analysis to answer this question. Stable isotope ratios of elements such as carbon, nitrogen and hydrogen vary across the environment in predictable ways, and therefore provide an indication of geographic location and environmental conditions. Animals incorporate these isotopes into their growing body tissues when they eat or drink. Since Willow Warblers moult during the non-breeding season, collecting samples of winter-grown feathers allows stable isotope analysis to be used to look for differences in location and timing of moult between and within breeding populations. Results showed that Willow Warblers breeding in Scotland had different feather stable isotope signatures to those breeding in eastern England. While pinpointing exact wintering locations of birds is not possible from these data, the regional stable isotope differences may reflect variation in the birds’ diet and location during moult, and/or the timing of it. Such differences could mean that UK-breeding Willow Warblers are exposed to non-uniform environmental conditions, which could influence subsequent breeding success and survival rates.

Links to more studies from ConservationEvidence.com

Would you like to search for another species?

Share this page