BirdTrack migration blog – early spring

Looking back

Waxwings

The talking point for many birders over the colder months was the influx of Waxwings that began at the end of October and continued throughout the winter. The larger flocks seen across Scotland at the start of the influx began to split as birds headed south and west in search of food. By early January, many of these flocks had reached the southern half of Britain and Ireland.

In mid February, these flocks began to head back north and east in preparation for their crossing over the North Sea to Fennoscandia, ready for the approaching breeding season. It’s still worth keeping an eye on any trees and shrubs that hold berries in case they are visited by these Waxwings before they depart. At this time of year, they will also fly-catch from the tops of trees to supplement their diet, especially if berries are in short supply.

Bramblings

It was a poor winter for some other traditional winter visitors, though. Reporting rates for Brambling were below average and significantly lower than those in the winter of 2022/23, which was a good season for this smart relative of the Chaffinch.

As with Waxwings, the numbers of Bramblings spending the winter in Britain and Ireland can vary, and their distribution is often related to the availability of their preferred food supply – in this case, beech mast and birch and spruce seeds. This winter, a ‘mega flock’ of some four million Brambling was seen in Switzerland, which could be where some of the Brambling that would have wintered here ended up.

Gulls

Both Glaucous and Iceland Gulls were recorded in lower numbers compared to recent winters, which is a bit of a surprise given the blasts of arctic air that many of us experienced throughout December and January – these cold northerly winds are usually ideal weather conditions for the arrival of these gulls. Of those that were found, the majority were the typical first-winter birds, but the occasional smart adult was also picked out.

The bulk of the arrival, as would be expected, was across northern Scotland, particularly the Shetland Islands – some sites hosted multiple birds as well as individuals of both species. A few individuals did make it further south, though, with birds reported as far south and west as Cornwall.

Among these more southerly records were a few Kumlien’s Gulls, a subspecies of Iceland Gull that breeds across north-eastern Canada. It is a reasonably common vagrant to British shores although identification can be tricky. Kumlien’s Gulls usually have darker primary feathers than Iceland Gulls, but this plumage feature is extremely variable and some pale individuals are virtually indistinguishable from Iceland Gulls.

Swans

The numbers of Bewick’s Swans seen across the country were also lower than normal. A close relative of the Whooper Swan, which is present throughout most of the UK in winter, Bewick’s Swan is mainly restricted to southerly regions, and the west and east coasts of England. However, recent years have seen fewer and fewer Bewick’s Swans wintering in the UK, especially in mild winters like this one.

This trend is partially explained by short-stopping, a phenomenon where birds don’t travel as far on migration and spend the winter further north and east. Migrating a shorter distance is less energetically costly than travelling to the UK, and this wintering strategy is becoming increasingly viable due to climate change: less snow cover and warmer temperatures increase food availability in historically colder regions that are much closer to the birds’ breeding grounds.

Bewick’s Swans are one of the first winter visitors to migrate back east and reports had already started to fall away in mid February. By now, at the beginning of March, the majority of birds will have left.

Scarcities and rarities

Despite the low numbers of some of our favourite winter visitors, there were a few rare species to brighten up those dark winter days.

The top spot for many birders was the discovery of a Northern Waterthrush – actually a warbler species – in a residential area of Essex. It was initially found in the observer’s garden, but its preferred feeding area nearby was soon discovered, and a steady stream of admirers travelled to see this American vagrant.

Other standout rarities included a Sociable Lapwing in Cornwall, three Baikal Teals (a male and female in Somerset and a first-winter bird in Durham), and a Black Scoter in Norfolk. The Black Scoter was a first for the county but was almost expected given the large numbers of Common Scoter and Velvet Scoters seen off the North Norfolk coast this winter.

Looking ahead

The first spring migrants have already made landfall here, with an Osprey seen flying over a site in Suffolk on 4 February. A Wheatear was noted in Shropshire on 6 February, and a Swallow was seen in Dorset three days later, closely followed by a Sand Martin in Kent the next day.

Over the next month, the pace and intensity of migration will steadily increase. Expect to see a mix of birds arriving here to breed – like warblers, Cuckoos and hirundines – and other birds departing as they head to breeding areas further afield – like ducks, geese and swans.

Seabirds

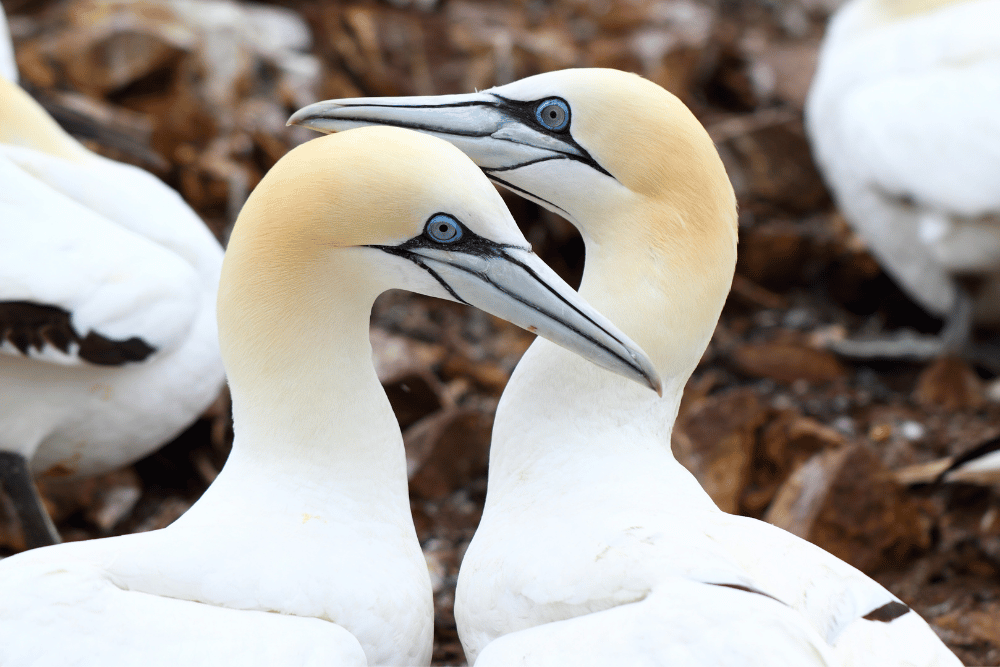

Seabirds such as Gannets, auks, and Fulmars will be scoping out their breeding cliffs and reuniting with their mates in preparation for the coming breeding season. Some sites have already seen numbers of Gannets building and pair bonds being reestablished. More birds will soon join them: older birds typically arrive first, while younger birds and first-time breeders arrive later.

Rafts of auks, including Guillemots and Razorbills, will be slowly building on the seas around their breeding cliffs, ready to venture back to the cliff ledges to find a place to lay their eggs.

Many of these birds will already be in breeding plumage, with their sooty, smudgy grey-and-white winter plumage replaced by smart tuxedos. This transformation is particularly impressive in Black Guillemots, whose immaculate black feathering of summer plumage is accentuated by a crisp white wing patch and red legs and gape.

Seabird colonies have been hit particularly hard by highly pathogenic avian influenza over the last few years, with devastating levels of mortality seen in Great Skua and Gannet populations in 2022, and in gulls, terns, Kittiwakes and auks in 2023. We watch their return to their breeding colonies with a degree of apprehension – let us hope this year sees a change in their fortunes.

Wildfowl

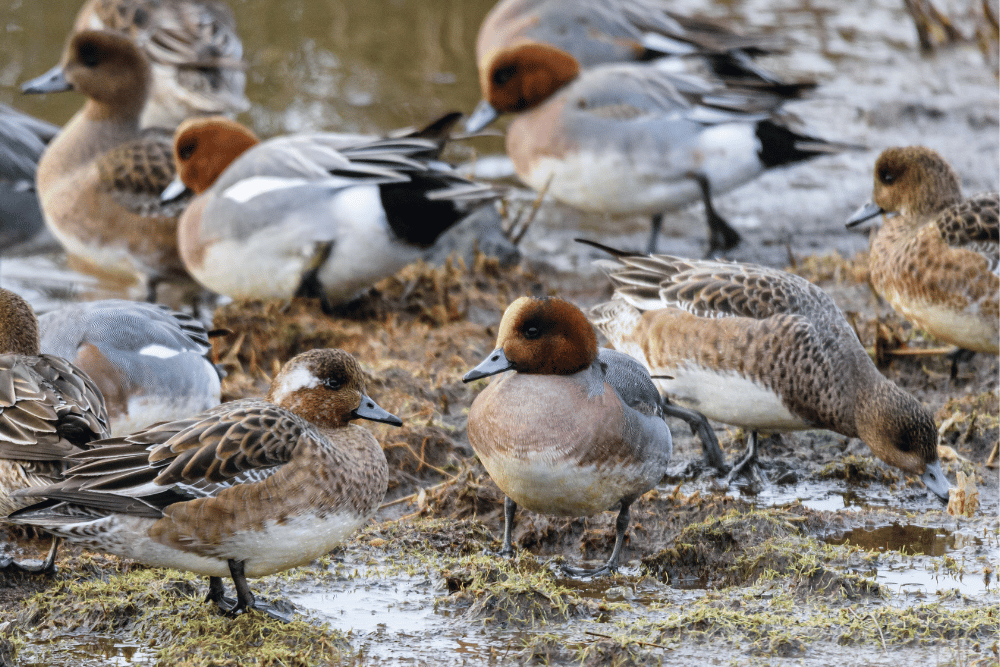

Flocks of wildfowl will be moving across the UK, with mixed groups of Teal, Wigeon, Pintail, and Shoveler moving back north and east in readiness for the North Sea crossing to their breeding grounds. Some will already have made this journey, while others may have attempted it only to turn back due to unfavourable wind directions.

White-fronted Goose and Taiga Bean Goose are the first of our wintering geese to start heading back to Fennoscandia and arctic Russia, with the bulk of the birds leaving Britain and Ireland by early to mid March. Other goose species, such as Dark-bellied Brent Goose and Pink-footed Goose, have a much more protracted migration period, with birds remaining here well into April in some regions.

On calm nights, listen out for ducks and geese migrating overhead, even at inland locations. Species as unexpected as Common Scoter – usually seen offshore – have been reported in landlocked counties through recordings which have captured their nocturnal flight calls.

Gulls

Throughout March, Common Gulls will continue to head back north. A small proportion will stay and breed in Scotland and Ireland, but the majority will be heading for Iceland, Fennoscandia, and other areas of north-western Europe.

While numbers of Common Gulls fall away, reports of Mediterranean Gulls are likely to increase as birds arrive from Europe. Once a scarce bird across Britain and Ireland, this species can now be found breeding at several locations and is slowly spreading northwards.

The Mediterranean Gull’s clean black hood, blood-red bill and white primary feathers make for a very smart bird, and their “yaa-uh” call is very distinctive.

Waders

March is a transitional time for most waders; Turnstones and Grey Plovers will be departing, while – a little later in the month – Little Ringed Plovers and Whimbrels will be starting to arrive.

Little Ringed Plovers are one of the first spring migrants to land on our shores and are considered by many as a sure sign that summer is not far away. Many of the birds seen in April will stay in the UK to breed across much of England, south Wales, along the east coast of Scotland and throughout the Scottish Central Belt.

Whimbrels, however, are extremely scarce and localised breeders in the UK, with only a few populations in Shetland, Orkney and the Outer Hebrides – the majority of birds seen around the coast in spring will be passing through on their way to their arctic breeding grounds, which stretch from Greenland to Siberia.

February and March are also good months to see Oystercatcher. This striking black and white wader is familiar to many of us, and soon birds will be pairing up for the breeding season, chasing each other around and duetting with each other to establish pair bonds.

Passerines

By mid March the first spring passerines will be arriving. Some of the earliest include Black Redstart and Firecrest, both scarce breeders in Britain and Ireland and very welcome because they hint at what is to come.

Black Redstarts can turn up anywhere but have a habit of appearing in derelict urban areas and building sites as well as scrubby patches along the coast. This same scrub can play host to Firecrests and often the two species can be seen in the same area.

The high-pitched call of Firecrest is similar to that of the closely related Goldcrest but is more direct, and has a tone akin to that of a Kingfisher’s call. The dark eye-stripe and white supercilium (a stripe above the eye) also help separate the Firecrest from the Goldcrest, which has similar plumage but a much plainer face.

Wheatears arrive at a similar time as Firecrests and Black Redstarts. British-breeding birds (Oenanthe oenanthe oenanthe) are the first to arrive, heading straight back to their upland breeding areas before birds of the Greenland race (O. oenanthe leucorhoa) pass through in April. Males of the British-breeding population have a bluish-grey back and head, while those of the Greenland population tend to show more brown tinges to the feathering on the back.

By the end of March, Sand Martins will be arriving in greater numbers but being reliant on insects, they can be badly affected by cold snaps. Often, birds arrive and then move back south if the weather turns colder, waiting in warmer regions where their insect prey is more plentiful.

Areas of open water, especially those surrounded by reedbeds, are good places to find your first Sand Martins of the year, and who knows, a Swallow or House Martin may even be accompanying them.

Scarcities and rarities

Scarcer species to keep an eye out for in early spring include some ‘overshoots’ from the Mediterranean – those birds which, having wintered in areas south of Europe, journey a little too far north on their migration and find themselves on UK shores.

Such species include Hoopoe, Alpine Swift, and Black Kite, or possibly something rarer like Great Spotted Cuckoo.

Other rarities that have turned up in early spring include Little Crake, Gyrfalcon, Crag Martin, and Alpine Accentor.

Send us your records with BirdTrack

Help us track the departures and arrivals of migrating birds by submitting your sightings to BirdTrack.

It’s quick and easy, and signing up to BirdTrack also allows you to explore trends, reports and recent records in your area.

Find out more

Share this page