Celebrating PJ

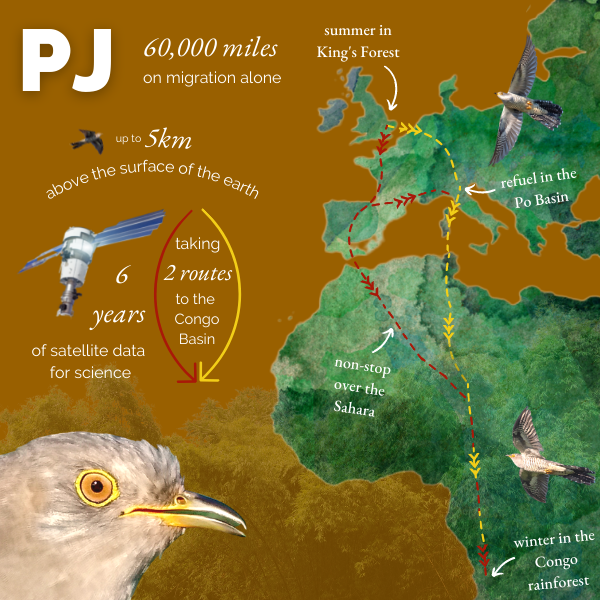

One bird, 12 journeys, 60,000 miles and invaluable scientific data: PJ the Cuckoo has left an incredible legacy.

I first met PJ when he was having his satellite tag fitted in King’s Forest, Suffolk, little knowing that this would be followed by many more encounters over the years. He was named by the family of Pamela Joy Miller, sponsored in memory of her love of birds and the joy they brought her. She passed this love on to her children and grandchildren, who were able to follow all of PJ’s migration journeys.

We have no idea how much information we are going to get from any of the Cuckoos when they are first tagged. They all give us valuable data about how environmental conditions affect survival, but as ‘Cuckoo followers’, we hope that we will see at least one whole migration from the UK to Africa and back again. This isn’t always the case, though – we have lost some birds before they have made it to the Channel, and others in southern Europe before they made it to their wintering grounds.

PJ’s greatest legacy, for me, is the way he engaged an enormous number of people in BTO’s Cuckoo Tracking Project as they followed him on migration.

This wasn’t to be with PJ. He became a record-breaking Cuckoo in the summer of 2021, completing the most migratory journeys of any tagged bird of this species. This year, he surpassed his own record, completing his sixth complete migration from the UK to Africa and back again whilst wearing a transmitting satellite tag, and clocking up over 60,000 miles.

During his time, PJ taught us that Cuckoos aren’t always tied to a single route to Africa – he followed both a path through Italy and through Spain on his way south across the years. He taught us that it’s possible to follow a Cuckoo with a satellite tag over several seasons, and that timing is everything – there is probably a lot of luck involved, but PJ seemed to have an uncanny knack for avoiding the worst of the droughts that southern Europe experienced during his migrations, as well as the sandstorms, the unseasonable snow, the hail storms and the late springs in the UK, where temperatures were not the best for a bird that spent most of its life in the Tropics.

The oldest recorded Cuckoo lived just under eight years, so I had known for a while that PJ was getting closer to the end of his life. Even so, hearing of his demise in his breeding territory was tough. I shouldn’t anthropomorphise, but PJ was like a friend, coming back to the forest just a few miles from my home, a friend that I would make the effort several times each summer to greet and marvel at as he chased female Cuckoos and defended his territory against rival males. At these times he always seemed so alive and in my mind, very much in charge of his bit of King’s Forest.

I will miss PJ more than I thought I would, and his little bit of King’s Forest will never be the same again, but he has left an enormous legacy. I am in no doubt that he has offspring that will be in and around the forest for years to come, but his greatest legacy, for me, is the way he engaged an enormous number of people in the BTO Cuckoo project as they followed him on migration, checking his journey on the BTO website, reading about him in the monthly updates and seeing him in the national newspapers.

PJ was a truly amazing bird – rest in peace, my friend.

Paul Stancliffe

British Trust for Ornithology

Share this page